Industrial Design Archives Project

Industrial Design Archives Project

Designer Testimony 03

Living the Showa Era design experience

Kumagai Kazuo

Born in Osaka in 1928, Kumagai Kazuo graduated from Osaka municipal Kogei Senior High School in 1946 and went to work for Hankyu Interior Decor Co., Ltd. After that, he worked for Kinki Advertising Co., Ltd., then joined Sanyo Electric Co., Ltd. in 1951. At Sanyo, with Sawada Shigetaka and Koba Hikaru as his advisors, he worked in advertising and was involved in corporate brand creation. When Sanyo established its Industrial Design Department in 1961, he moved to that department, which was headed by Naoki Tominaga. In 1975, the Industrial Design Department changed its name to Design Center, and in 1984 Kumagai became the director of the Design Center until he retired from Sanyo Electric in 1988. Until 1998, he guided and encouraged young designers as a professor of visual design at Takarazuka University of Art and Design (now Takarazuka University).

Immediately after World War II, Osaka and its people were exhausted. At a time when the word “design” was not yet widely recognized in Japan, Kumagai Kazuo began acquiring the occupational skills of a designer as he racked up one relevant experience after another. His story eloquently conveys how the postwar Showa era created work that was called “design,” and what kind of “design” work that was. Still young when he changed jobs to join Sanyo Electric in 1951, he was on the scene as one of the advertising team for the launch and resounding success of the industry’s first plastic radio (SS-52) in 1952 and the first made-in-Japan pulsator washing machine (SW-53) in 1953. He started out working at the advertising desk in the sales department. His position would be called “graphic designer” in today’s terms, but by happenstance he ended up being transferred to the Industrial Design Department. This was a different world, which encompassed the unfamiliar territory of product design and industrial design. Nevertheless, Kumagai eventually became director of the Design Center. He coordinated a team of designers whose numbers increased beyond comparison with the number of designers at Sanyo when he joined the company, and he led the build-up of the Sanyo brand. In those days, there was no clear path for someone to aspire to be a designer, learn design, then work as a designer. This third installment of IDAP’s “Designer Testimony” series presents some of Kumagai Kazuo’s stories from the early days of his career, and introduces the environment that influenced design in that era.

World War II and Osaka Municipal Kogei Senior High School

In 1942, I entered the woodworking design department at Osaka Municipal Kogei Senior High School (now Osaka City Kogei High School ). I suppose I was influenced by my father. My father was a self-employed designer—today he would be called a graphic designer—and since he worked at home, I was always watching him. Most of my second year of high school was spent doing factory work under the government’s labor mobilization program. Even the teachers were sent out to work, and the school was shortened from a five-year program to four years. However, in 1946, after the war was over, the school went back to the five-year system. I was due to graduate the four-year program that year, but had the choice of graduating after 4 years or staying on for a fifth year. I took the entrance exam for Kyoto College of Technology , which at that time was called the Kyoto Vocational College of Technology (Note 1), and is now the Kyoto Institute of Technology. I’m ashamed to say that I failed to get in. The Kyoto College of Technology had no design department at that time, so I took the test for the architecture course, but the level was way too high for me. So I didn’t get past the front gate! I decided that my best course of action would be to stay on at Osaka Kogei and complete the five-year program instead.

Note 1: During the war, in 1944, Kyoto College of Technology was renamed Kyoto Vocational College of Technology, and the design program was changed to an architecture program. In 1949, the Kyoto Vocational College of Technology and the Kyoto Vocational College of Textile Fiber (originally the Kyoto College of Textile Fiber) merged to create the Kyoto Institute of Technology. The industrial design department was established in 1954.

What was your first job?

Our house had burnt down in the war, and life was not too easy. At that time I found a newspaper ad for a job at Hankyu Shitsunai Soshoku (a Hankyu company handling interior design). I was hired, and began in the designing section, where my job was to produce drawings. The company’s main work was designing and manufacturing custom furniture that was ordered from Hankyu Department Store as well as design and fabrication related to interior décor for theaters managed by Toho, like Takarazuka Grand Theater, Umeda Theater, OS Theater, and Kobe Sannomiya Theater. Umeda and Sannomiya were almost totally destroyed in the war. A lot of work was involved in reconstructing them. The biggest project of all of them was the restoration of Takarazuka Grand Theater after the US military derequisitioned it. About half of our work was Takarazuka.

What kind of work did you do?

I was mainly involved with advertising that we placed on and around the stage and on the panels and other displays in the lobby. The stage had drop curtains and sleeve curtains on the sides, and they all carried advertisements. Also, for example, there were advertisements on the backs of the auditorium seating. At that time, there were a lot of ads for Pias cosmetics and things like that.

Classic stage curtains were generally tapestries, but in those days we couldn’t spend so much, so we had something called a kaki-wari stage curtain, made of flats that we painted to look like a tapestry. We used the kind of thick canvas that tents are made of, and enlarged a Syrian pattern produced by Japan Fine Arts Exhibition artist Sano Takeo. We didn’t have a large workspace, so we spread out the canvas in the hall of a temple in Kyoto. We took buckets of paint made from iwa-enogu mineral pigments mixed with a casein binder, and seven or eight people painted the design using stiff brushes, like scrubbing brushes. I think it took about two months. When it was more or less finished, Professor Sano came to check it. It was so big that you couldn’t see the whole thing by standing in front of it, so we took the canvas out of the hall and he climbed a tree to get to a height where he could look down at it.

With the stage curtains for the Umeda Underground Theater and the other smaller theaters, I was given a free hand to do the design myself, from scratch. At that time, I made them using appliqué. All told, I worked there for about a year and a half, but once the theater reconstruction work started to wind down, I decided to quit. After that, I joined an advertising agency called Kinki Advertising (which later became Daiko Advertising).

How did you come to join Sanyo Electric?

While I was working for Daiko, I received a phone call from my former teacher at Osaka Kogei, saying “Why don’t you come over and visit?” That led to an introduction to Sanyo. Sanyo Electric had started as a small manufacturing plant, but had recently incorporated as a joint-stock company, and was growing fast. Its head office was cramped. When I visited the company and met the managing director, he said “Right now I don’t have anywhere for you to sit, but soon our new head office building will be ready. Can you come back then?" I think it was May of 1951 when I joined Sanyo Electric. I was assigned to the advertising desk in the Sales Department. At that time, I think there were probably fewer than 100 employees in the head office.

So you joined the year before the launch of the SS-52 plastic radio…

(Looking at a photo of the promotional truck for the SS-52 plastic radio) In the days when we made this promotional truck, nobody used to think about who was responsible for which job. My boss, Mr. Kawamoto, and his older brother, who was the manager of the Niwakubo plant, were involved in making the truck, and I went to the work site along with them. Using Toyota’s latest model truck to provide the chassis, they made a special body at a sheet metal workshop in Minato-ku, Osaka. From the outside, the truck body looked exactly like a bigger version of the SS-52 radio. Promotional vehicles were rare at that time, and it attracted a lot of attention as it roamed throughout Japan, broadcasting commercials along the way. At that time, Sanyo’s products included first of all bicycle generator lights, bicycle locks and electric bicycle horns, as well as toasters and blenders. Then there were radio parts, like speakers, variable capacitors, and intermediate frequency transformers. In other words, we already had the foundations for making radios.

Japan’s first plastic radio, the SS-52 (1952)

Promotional truck in the form of a giant plastic radio mounted on a truck bed

SW-53, the first made-in-Japan pulsator washing machine (1953)

How much awareness of industrial design was there?

My viewpoint may be biased, but Osaka Kogei and schools like it were providing a very high level of education. So, people specializing in design learned about Bauhaus and such, and were aware of the public role of design. So there was awareness, but there was no formal recognition of design in terms of professional skills.

What about branding?

The first general manager of the Advertising Department (Kameyama Taichi) was highly invested in the relationship between management philosophy and advertising, and in the approach that advertising should take. He headed a monthly advertising planning meeting with the brains of the advertising team, Sawada and Koba, and at these meetings we also discussed what the nature of our brand should be. For example, noting that Matsushita Electric’s company name was Matsushita Electric, its brand was National, and its corporate symbol was pine needles, we discussed whether, as a similar type of company, Sanyo should take a similar approach. Our discussions about company name, brand, and corporate symbol were in effect pioneering attempts to develop what is now known as corporate identity. And we decided on the company motto: ” Precision craftsmanship to be proud of the world over.” That was when we made a full-page ad for the New Year newspapers. Product advertisements were most common, but corporate advertising was beginning to appear. I suppose it was around 1960.

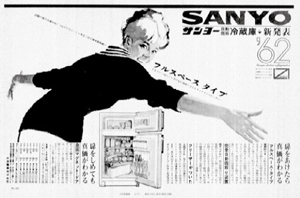

Newspaper advertisement for new type of refrigerator Illustration by Sawada Shigetaka, 1961

Sanyo’s Industrial Design Department

I believe our president (Sanyo Electric president, Iue Toshio) ended up meeting Tominaga Naoki after he asked Sekisui Chemical Co., Ltd. to mold plastic cabinets for radios. I think Iue intuitively felt, “Sanyo needs this person,” and he persuaded Tominaga to come to Sanyo. The in-house newsletter printed a discussion about design between them.

Even before the establishment of the Industrial Design Department, employees who were involved in product design used to discuss industrial design. The company newsletter published some of their thoughts, too. They all had a keen awareness of the importance of design.

After that, the Industrial Design Department was finally established within the head office. It tried to play the role of what you could call a design center, but the reality wasn’t so simple. At that time, designers who were assigned to specific factories did not necessarily have a job title associated with design. They had all sorts of positions. Organizationally speaking, the Industrial Design Department was positioned as part of head office, but Takai Ichiro—who subsequently transferred from Sanyo to Kyoto City University of Arts—would often debate the wisdom of that with Tominaga and with us. The discussions boiled down to a question of whether design is a staff function or a line function: “Are industrial designers involved in administration or in production?” Put another way, the debate was about whether designers belonged in the head office or the factory. The conclusion was…that there was no conclusion to be reached. The best I can venture is to say that the head is part of the office staff, but the body is associated with the production line.

If you work in a factory all the time, and then you move away from the factory, the foundation of your work collapses. That might make one think that the body should stay in the factory, but when you are in the factory, you can’t help but place priority on manufacturing ease or convenience. But the head office says, “don’t concentrate on designing things that are easy to make,” and emphasizes that you should design for the people who will use the product. However, the more they say that, the more resistance there is. That’s why Tominaga’s presence was so important. Even if there was resistance from the factory, when he said “no,” no one could argue. But as to whether or not the manufacturing people were really convinced— that’s hard to say.

While I still worked in advertising, I once took Naoki Tominaga around the Hojo Plant (a Sanyo Electric factory in Kasai, Hyogo Prefecture). Why was a low-level employee like myself, who had only been with the company for two years, assigned to accompany him? Well, maybe he needed someone who understood design at his side. I don’t know if that encounter was the cause or not, but I was transferred to the Industrial Design Department when it was established. As a result, I was still working in design, but I moved from flat surfaces to three dimensions, where I was still an amateur. Nowadays visual and industrial design are considered to be two separate fields, but at that time there were many people who moved from graphic design jobs to careers in industrial design.

Note 2: Sculptor Tominaga Naoki was known for designing the Type-4A telephone for OKI Electric Industry Co., Ltd. He served as an industrial design advisor to OKI and Sekisui Chemical before being appointed as an advisor to Sanyo Electric in 1955. When Sanyo established its Industrial Design Department in 1961, Tominaga became the department’s director, and later served on Sanyo’s board of directors.

Sanyo’s first refrigerator, SR-350 (1957)

Advertisement for the 19-CT1000 color television (1967)

Design at Sanyo

Sanyo was a new company. At that time, the Electronic Industries Association of Japan formed a design committee. I think it was Toshiba who proposed it, and Toshiba certainly played a central role. Tokyo had the Big Three—Toshiba, Hitachi, and Mitsubishi Electric—as well as Sony and various others. The Kansai region had only three household electrical appliance manufacturers—Matsushita, Sharp, and Sanyo—and Sanyo was the newest. I think Sanyo was the most innovative in terms of design. Since the company wasn’t old, there were no old aspects to it. It was a company where designers were allowed to work as they saw fit. For example, as an experiment, we designed not only shapes that we expected to see five years into the future, but also designs based on functions we expected to see in that future. We would think what sort of technology would probably be available in another five years. Sanyo had room for that kind of imagination, and I think it provided a foundation for various series of products.

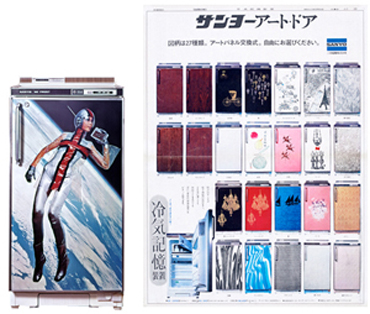

Sanyo launched a variety of series of products, such as the it’s series that was aimed at consumers who live alone. Please tell us about the Art Door series of refrigerators that Sanyo began offering from 1965.

If you look at how refrigerators are made, leaving aside the main body, the structure of the door changed from the conventional box shape formed by stamping to a wrap-around structure. This involved sandwiching a layer of urethane foam insulating material between the outer panel and the interior, molded panel, and surrounding the outer edges with aluminum sash. As a result, we began to see doors with the appearance of wood-grain. And if the door panel could be made to look like wood, it was also possible to apply a variety of other patterns. In other words, the manufacturing method made it possible to produce artistically decorated units, which led to the Art Door refrigerators.

In the latter 1960s and early 1970s, we began to see floral-patterned products. Tiger was first with a floral-patterned vacuum flask. Sanyo started with a toaster (SK-300) and an electric kettle (U-300).

Art Door refrigerator lineup, 1965

Interviewer/editor: Ueki Keiko, Nakanoshima Museum of Art Osaka Planning Office

* Titles omitted in profiles, annotations, and supplementary explanations to interviews set in parentheses.

This Designer Testimony series presents digests on specific themes from the oral histories being recorded for the Industrial Design Archives Project (IDAP). IDAP plans to publish its oral histories in detail in reports and other formats.