Industrial Design Archives Project

Industrial Design Archives Project

Designer Testimony 01

Unobtrusive excellence

—The triangle tap, a pinnacle in design

Kachi koen

Born in Gifu Prefecture in 1934, Koen Kachi joined Matsushita Electric Works, Ltd. in 1959 after graduating from Kanazawa College of Art. He was responsible in particular for designing, developing and ensuring the safety of wiring devices required to support the rapidly expanding household electrification of that period. In 1962, he was involved in the development of triple taps and triangle taps, and helped Matsushita Electric Works win its first G Mark Good Design Award in 1964. In 1982, he became director of the company’s Corporate Design Center. He later served as general manager of the Tokyo Planning and Development Department and the Design Department, focusing his energies on training the next generation of designers and transforming the company’s design organization. After retiring in 1994, Kachi established Tasuku Design Planning, where he continues his life work of supporting everyday life through design based on the support he himself has received from others.

In 1962, Matsushita Electric Works released two little products created by a young designer who had joined the company only four years earlier. By 2010, the company had sold a combined total of over 100 million of the two products, which even today, over half a century on, continue to be sold in much the same form as when they first came out. Playing an important but inconspicuous ‘wallflower’ role in households and workplaces throughout Japan, they will be a familiar sight to most people, but surprisingly few people know their names—triple tap and triangle tap.

These two multiple outlet taps represent what could be seen as a pinnacle in design, becoming such an integral part of our lives that they are just taken for granted, almost unnoticed. In this, the first installment of the Industrial Design Archives Project’s Designer Testimony series, we talk to Koen Kachi, the industrial designer who created these long-selling products.

High Triple Tap WH2013

High Triple Tap WH2013

High Triangle Tap WH2012

High Triangle Tap WH2012

First of all, how did you come to join Matsushita Electric Works?

I joined Matsushita Electric Works after graduating from Kanazawa College of Art, but before that, I was studying engineering at a junior college that was a part of Shizuoka University, with the intention of becoming an engineer. I was crazy about cars, and wanted to go work at Honda. One of Japan’s first industrial design competitions was held at that time, with Yanagi Sori winning the top prize. There was also a professor on our campus fresh from a spell in the USA, and he said to me, "Mark my words, design will soon be taking off in Japan as a new profession." I was fascinated, and decided to change course. I was the youngest in the family, and tended to get easily carried away, but my older brother, who had survived the war, encouraged me, saying, "If it’s something you really want to do, go for it!" So with my family’s blessing, I switched to Kanazawa College of Art, where Yanagi Sori was teaching. Around 1958, Matsushita Electric Works began offering summer internships as part of their recruitment strategy. They would put out a call for fourth year students to train as interns over the summer holidays and recruit those who showed promise to join the company the following spring after graduation. I was one of the first designer interns. The college had recommended me for the internship, which required me to spend the summer holidays in Osaka. I got hired, but apparently only after the company’s first choice went elsewhere!

Did you start working as a designer as soon as you joined the company?

After joining the company in 1959, I was posted to the factory in Tsu, right from the start as a designer in the Design Department. The Tsu factory was where sockets and other products that Matsushita had produced since its founding were manufactured, and urea resin molding was the main operation there. However, in the autumn of the same year, the company transformed to a business unit structure, and I was assigned to the Wiring Devices Division and transferred to the company head office in Kadoma City, Osaka Prefecture.

What kind of work did you do as a designer in the company at that time?

Our job was to develop new products, but rather than just focusing on design alone, we were expected to have our finger on the pulse of the era and design products that anticipated trends. In the Wiring Devices Division, the design team was part of the General Planning Group, so we were close to the people responsible for planning products. When we all got talking together someone would often say, "How about something like this?" Before long, I would started sketching and offering various suggestions. We’d also ask whether there was anything else we could do to help develop the wiring devices market. It was the sort of place where you could discuss anything freely.

Wiring devices are really simple. Sure, it’s electrical equipment, but it wasn’t as if we were developing fluorescent lights. Our job was to make switches that anyone—children, grandma, or grandpa—could operate. Whatever I tackled, my departure point was, "easy to use, easy to understand."

What is the scope of the work of a designer?

Were you involved in designing the technical innards as well as the external appearance?

I think industrial designers have to do that too. We don’t just design product covers or decorative features. When we design the external form, we think about the concept and the structure required to make it a reality.

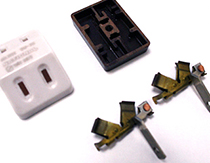

This triangle tap has two metal parts inside. (Kachi opens the tap with a screwdriver.) They’re actually identical, and just flipped between left and right. And this black base is the same as the base of the other product, the triple tap. Both products use the same part. Enabling the same molds to be used boosts productivity and cuts costs. As designers, we too need to think about such aspects.

Triangle tap parts

Triangle tap parts

Can you provide more details on the triangle and triple taps?

I designed these two taps shortly after joining the company. It was a time—the late fifties and early sixties—when all sorts of consumer electrical appliances were coming on the market, so there was a need for wiring devices of proven quality that was easy to produce. If the products were easy to produce, we could keep prices down. At that time, carbon was added to the urea resin used to make the products, so they would be blackish as a result. That made them conspicuous. If if they were white, they would still be noticeable, but could be used on any wall without being too obtrusive. But the idea of making them white met with quite a lot of opposition. "White? You’ve got to be kidding!" The reason was that white makes quality assurance really difficult. If the kind of dust that would pose no problems with black products contaminated white products, they would be rejected as defective. But I stuck to my guns, and in the end we succeeded in doing what everyone thought couldn’t be done. I think our quality assurance people also gained confidence as a result.

How was your relationship with the manufacturing and quality assurance sides?

I suspect they thought, "Oh-oh, here comes Kachi with another brain twister!" (laughs)

After the white taps, I started working on full color wiring fixtures such as switches and sockets, which started people off again. "Might have guessed you’d be back with other colors after pure white." "What’s with all these colors and asks? There’s a limit, you know."

What was really great about that time, though, was the company dorm. No matter what site or section you were assigned to, everyone lived together in the same apartment house for the first three years, and after work, we’d all meet up in the canteen, regardless of seniority. If you were worried about something, someone would always be there to lend an ear over a beer or two. When you all know each other like that, people are ready to give your ideas more room. That’s how the full color products came into being.

Full color series

Full color series

In other words, the dorm system created the kind of camaraderie that inclined people to at least listen to you.

There were also times when I was scolded by my seniors, but I still think it was a great way of breaking down the barriers between different sections. Particularly for a country lad like me, it was wonderful to be able to start off in a place that guaranteed meals and a roof over my head.

It sounds like there was a family atmosphere to the dorm. Did proposals tend to end up as products after being passed from the bottom to the top?

Oh yes, most happened that way. We owed that corporate culture to the president Niwa Masaharu more than anyone else.

In 1982, I suggested establishing a Corporate Design Center. Until then, each business unit designed products itself in line with their business plans, and this led to a lack of design uniformity and design policies for creating a coherent whole. Allowing people to do their own thing is of course important, but the company was growing bigger and bigger, and I felt the need for a more consistent, all-embracing corporate image. So I gathered a bunch of people together, and we all went for a few drinks at a bar in Nishisanso (near Nishisanso Station on the Keihan Railway) and tossed ideas around until we had something to take to the powers that be. When I took the proposal to the president, he said, "Okay, let’s do it" just like that, and that’s how the Design Center came into being.

So it sounds like you employees had a lot of freedom.

The president was an astute manager who knew how to get the most out of his people. He gave us free rein to put whatever talents we had to good use in a way that benefited the whole organization.

Both the triple tap and triangle tap are timeless products, their basic design barely changing since their release. When you first dreamed them up, did you actually have such long life and design durability on your mind?

No, not at the time, but I did want to create something that wouldn’t be too flashy, something that wouldn’t need to be changed. I made various prototypes with plaster, but both the design and the production technology side agreed that this was the best design.

They look very simple, but I suspect their design was shaped in various ways by careful consideration of user needs.

Well, we did pay a lot of attention to their grip. By making the cover larger than the base, we made the products easier to grip and pull out of a socket. This projection was absolutely intentional.

Kachi-san talked with us for a total of almost six hours at Panasonic Eco Solutions (formerly Matsushita Electric Works). Current employees, both designers and public relations handlers, sat in on the interview, making it more like an enthusiastic discussion on design with the products in the middle, punctuated frequently by laughter. No doubt Matsushita Electric Works’ dorm buzzed night after night with the same kind of jovial conversation.

Our thanks again to Kachi-san, who says with a glint in his eye, "I’m not that disciplined, so I’m always trying my hand at something new."

Interviewer/editor: Ueki Keiko, Nakanoshima Museum of Art Osaka Planning Office

This Designer Testimony series presents digests on specific themes from the oral histories being recorded for the Industrial Design Archives Project (IDAP). IDAP plans to publish its oral histories in detail in reports and other formats.