Industrial Design Archives Project

Industrial Design Archives Project

Designer Testimony 07

Flooring for the masses-Popularizing precious wood

Nakajima Tsutomu

Born in Kyoto in 1935, Nakajima Tsutomu graduated from Kyoto University Faculty of Agriculture’s forestry department in 1961 and went to work for Asahi Special Plywood Co., Ltd. (now Asahi Woodtec Corp.) He was mainly involved in research, product processing technology, and product development. In 1986 he received the 31st Japan Wood Processing Technology Award and the 18th Ichikawa Memorial Award. In 1989 he became Executive Director in charge of product development. He retired from the company in 1999. In 2001, he received the Japan Wood Processing Technology Association Kansai Branch Achievement Award.

Nowadays Western-style rooms are considered a completely normal part of Japanese housing and life. And the main thing that makes a Western-style room a "Western-style room" would be the flooring material. Many people laid carpet on top of tatami mats in order to convert a traditional Japanese-style room into a Western-style room. But Western-style wood or laminate flooring is much coveted as a material for covering floors, and all the more so when the material is real wood. However, it certainly is expensive.

The history of flooring materials in Japan coincides with the history of Japanese housing after World War II. We interview Mr. Nakajima Tsutomu, who devoted himself to the development of decorative veneer plywood while working for Asahi Special Plywood, which is now called Asahi Woodtec. Mr. Nakajima is not a designer, rather he is an engineer who specializes in wood. Nevertheless, we can see clearly that the products that were created as a result of his work constitute major elements that are indispensable to the design of residential spaces.

Joining Asahi Special Plywood

The company that is now called Asahi Woodtec was called Asahi Special Plywood back when I joined it. I studied forestry at the Faculty of Agriculture of Kyoto University, and the future that I envisioned was to become an official of the Ministry of Construction. As it happened, I messed up my national civil service exam, so I was not able to get into the construction ministry. A professor at the university recommended that I become a local-level civil servant in Shiga Prefecture. He suggested that I study for another year while working, then try taking the national civil service exam again, but that idea didn’t appeal to me. Just then, Kajita Shigeru, who taught a wood utilization class at the university and was known as an authority in wood processing technology circles in Japan, told me there was a company called Asahi Special Plywood in Osaka. He said, "The guy who runs it is extremely positive and has excellent management instincts, so why don’t you go there?" He gave me an introduction, and that’s how I ended up joining the company. It really came about because of a chance encounter. When I joined the company, it had about 120 employees.

Asahi Special Plywood specialized in making decorative plywood from natural, precious wood by using a slicer—a cutting machine that resembles a large carpentry plane—to cut thin pieces of wood veneer from squared timber (called a flitch), and gluing the veneer onto lauan plywood. Asahi did not manufacture the lauan plywood base itself. The plywood that serves as a base was purchased from Japanese plywood manufacturers.

I joined the company in 1961, which was the tenth year after the company was founded. It’s a subsidiary of Shimotora Meiboku, a lumber merchant that handles and sells only natural timber products made from precious wood. In those days, only certain people purchased and used precious wood products, but there seemed to be potential for greater use by the general public, so Asahi Special Plywood was established with "precious wood for the masses" as the company’s mission statement.

I have the impression that in 1961, ten years after the founding of Asahi Special Plywood, a housing market was finally taking shape in Japan. When thinking about how to bring precious wood to the masses, did you have intermediate buyers for your product? In other words, were there sales channels?

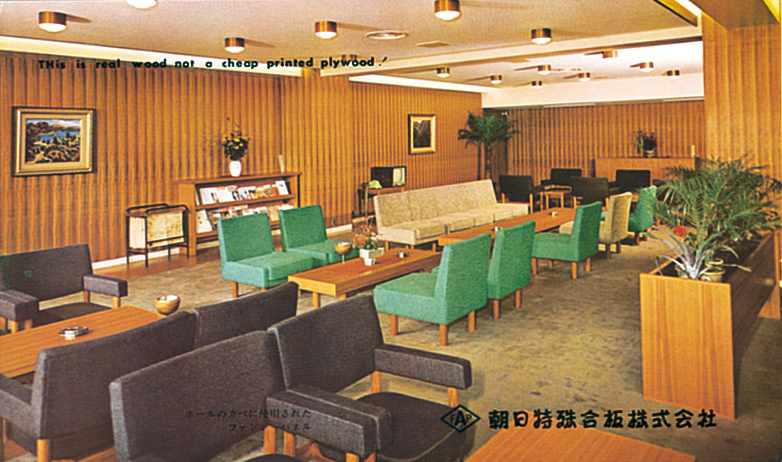

Normally the sales route for wooden building materials works like this: products made by building materials manufacturers are sold to a wholesaler, from there they are sold to a retail dealer, and from there to builders. Since this type of route did not exist at that time, it was extremely difficult to make sales and to keep the company going. Almost all of the buyers were contractors who handled interiors for commercial buildings, hotels, and other types of buildings, and they bought custom-made products based on design drawings

Asahi Special Plywood’s products are decorative veneer plywood made from precious wood as opposed to printed plywood decorated with printed designs. So you could call them high-end products, right?

Almost all of our products were custom-made to spec for non-residential buildings, but our company founder was determined to find a way to make standard products for use in regular housing.

For interiors in non-residential buildings, we supply products according to interior design drawings that include layout and dimensions, so the product dimensions are not constant. We end up supplying products with a variety of dimensions determined by each site’s interior designer. Still, the wood grain on the surface lines up nicely, and we end up with beautiful interior wall panels. It is possible to decorate a surface by using a "slip match" pattern, where the wood grain is arranged in the order in which the precious wood was cut, or a "book match" pattern where pairs of veneer face each other like pages in an open book. The products are made in a factory, but made to order. It depends on how you define "industrial product," but I don’t think of them as industrial products.

Even for private homes, as long as the client is willing to pay for it, it’s possible to produce products to spec. for decorative purposes. But when making standard products for residential use, the dimensions need to be constant, and it’s necessary to establish sales channels for such products. Each wholesaler covers a large area, while retail stores are responsible for smaller areas. In the old days, there were lumber dealers, and from them the products would flow to local builders. Even if we were to produce standardized products, without a sales channel the products wouldn’t be distributed, let alone reach a wider market.

On the manufacturing side, once we started making products with standard dimensions like 2 x 8 shaku (approx. 60 x 240 cm) or 3 x 6 shaku (approx. 90 x 180 cm), we saw the plywood factories follow suit and start to make corresponding products. Until that happened, there were no regular dimensions, so if somebody said, "Give me four meters," we would make four meters of plywood.

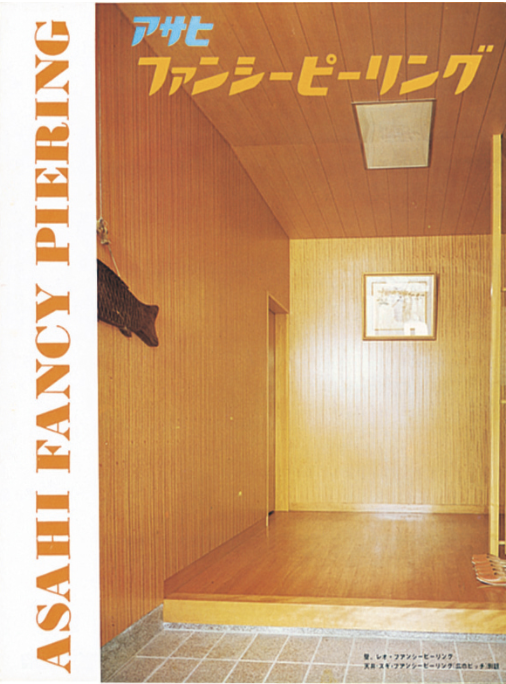

Fancy Piering (launched in 1958)

First precious wood decorative plywood in standard sizes

Paneling installed on walls

It seems there were many factors that had to be put in place. In the end, was the decorative veneer plywood still cheaper than solid wood?

Yes, it was. However, there’s one big problem that comes up when you compare our products to solid wood. Veneered plywood is made by slicing the veneer off a flitch and sticking it to the base plywood one piece at a time. Various wood grain patterns can be expressed depending on the gluing method. Japanese workers are highly skilled at applying veneer by hand, and they can make very beautiful decorative veneer plywood from natural precious wood. In the beginning, Asahi Special Plywood exported almost all of its wall coverings to North America in 4 x 8 shaku size (approx. 120 x 240 cm). The main market for wall materials was the United States. However, since the humidity in the United States is lower than in Japan, decorative veneer plywood made in Japan was developing surface cracks due to the dryness. Products made in the United States used thicker decorative material on the surface (1.5–2 mm) and were manufactured in a dry environment, so surface cracking was less likely.

Around the time I joined Asahi Special Plywood, the company was commended for contributing to the Japanese export industry, but every time we exported, we received many complaints that the product surface was cracking. I was given the mission of finding a way to keep the veneer surface from cracking.

Decorative veneer plywood that doesn’t crack

They told me, "You went to college. Solving this sort of problem is exactly what someone who specializes in wood materials should do, isn’t it?" I was determined to show that I could do the job, so I holed up in the laboratory and almost never slept.

But I happened on a solution when we took a company trip to Byodo-in Temple in Uji, Kyoto Prefecture. There is a big door in front of the temple’s Phoenix Hall, and there is a picture of Buddha painted on the back of that door. The Buddha on the back of the door is beautiful, but the face of the Buddha painted on the wall inside the building was riddled with cracks. Wondering why there was such a big difference between the two, I looked closely and saw that there was gauze stuck to the back of the door, and the picture of the Buddha was painted on the fabric. I had a flash of inspiration that I might be able to apply the same technique to my problem. Maybe this is how people make discoveries, through random coincidences like this.

The result of this epiphany was a method we called APOC, taking the initial letters from "Asahi’s Prevention of Cracking." The basic idea is to insert cloth between the base plywood and the veneer that is attached to its surface. A lacquered bowl doesn’t crack, does it? It doesn’t crack because the surface of the wooden bowl is covered with gauze, and the lacquer is applied on top of that. This method is called nuno-gise, and I applied it to the manufacture of decorative plywood. I wanted to know what kind of cloth was best, so I started researching cloth from scratch. I collaborated with a textile shop in Kyoto to choose the type of cloth to attach to the wood. But then the president of the company complained, saying "Don’t be so extravagant! Who ever heard of gluing cloth like this onto plywood?!" I needed some trick to bring down the cost more. Then the president came back and said, "Nakajima, if you’re going to do that kind of thing, use newspaper!" But the way the fibers are organized in newspaper is different from cloth, although it’s certainly true that paper is cheaper than cloth. So I went back to the drawing board and started researching paper. As a result, we acquired patents for cloth-based APOC (S-C APOC), and then paper-based APOC (J-P APOC) as well, in the United States, Canada, Germany, and Japan. These wall panels gradually went onto the market as standard products. In Japan, the use of home air conditioners became more common, and dryness started causing cracks to appear in decorative veneer plywood wall panels. As a result, demand has emerged for wall materials that do not crack in Japan, too.

Wooden flooring

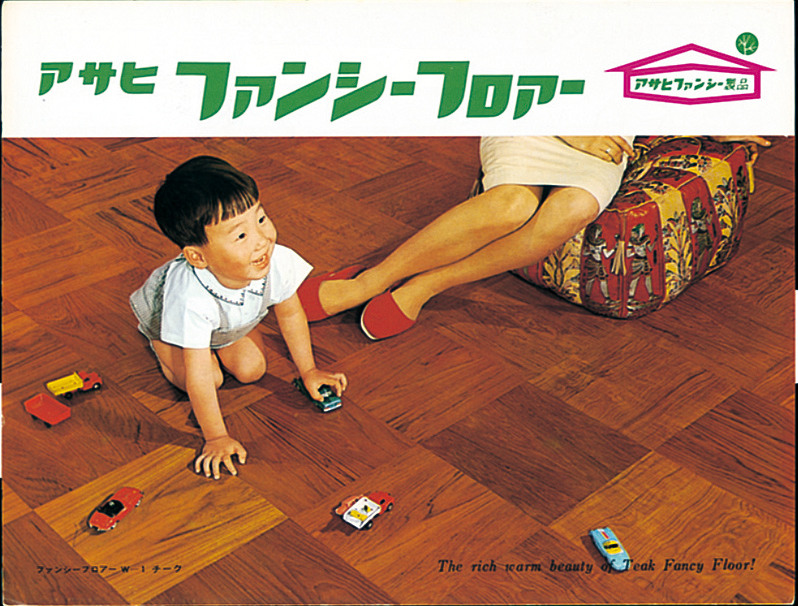

The norm in Japanese homes was to use tatami mats on the floor in Japanese-style rooms, carpets (generally needle-punch) in Western-style rooms, and vinyl tiles in the kitchen and other places where water is used. However, there were media reports about carpets being undesirable from a hygienic standpoint as they are prone to infestation by mites or ticks. Vinyl tiles had the disadvantage that they felt cold on the feet. In light of these issues, wood floors are increasingly the choice for Western-style rooms and kitchens in Japan. Initially, parquet flooring was popular for the wood floors. Pieces of teak and cherrywood, about 15mm thick, were put together and affixed to underlying floorboards. However, this entailed a lot of work, and was expensive. In order to offer lower-priced wood floors we took an approach similar to that used for wall materials and started to manufacture real wood veneer flooring. We assembled standard size pieces of wood into parquetry by making blocks of wood (flitches) 10cm thick and 30cm square, slicing those blocks into 0.3mm-thick veneer, and bonding the veneer to plywood. We commercialized this product with standard dimensions of 1 x 6 shaku (approx. 30 x 180 cm). It was 1960, and this signified the birth of decorative veneer flooring.

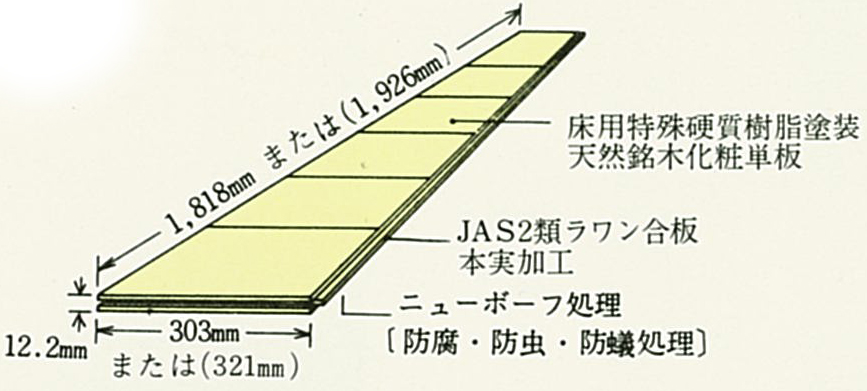

Fancy Floor (from 1960)

1 x 6 shaku (approx. 30 x 180 cm) floor material made from plywood with precious wood decorative veneer

The 1980s—adding color to wooden floors

Decorative veneer flooring became popular, mainly for the floors of Western-style rooms, but from the standpoint of homebuilders who think about the total design of a house’s entire interior, it was important that there be harmony between the color of the wooden floor and the colors of the walls, curtains, and other major elements. At first, due to our appreciation for the natural beauty of precious woods, we offered decorative veneer flooring only in natural colors. Then homebuilders Sekisui House and Misawa Homes approached us and asked if we could make decorative veneer flooring products that would enable overall color coordination throughout a home’s interior. Consequently, we began work with engineers from the two companies to investigate how to color our flooring products as an industrial process. It’s easy to talk about painting a floor, but using the normal production methods of that time would have meant just dumping on the color, so the color would not come out well and the product would have a poor finish. In light of those issues, I wondered if we could find a way to mechanize the kind of wiping method that is used for staining and finishing furniture surfaces, so that we could use it in factory production.

I had an intuitive sense that as a result of collaboration with these homebuilders, there would be growing demand for wooden flooring products that had been colored in the factory for use in normal homes. I went to the president and told him we needed to make colored flooring. Right away, he exploded at me, shouting, "What did you join Asahi Special Plywood for?!" And he continued, "To make precious wood accessible to the masses. And what people love about precious woods is their natural colors. Delivering that natural beauty is our chosen path. For you to suggest that we should paint colors on top of our beautiful wood… it’s outrageous!"

Does the addition of color really cause the individual expressions of the various types of trees to disappear?

No, it doesn’t. Moreover, it is very difficult to choose a tree species for the surface decoration of flooring material to match the color of the walls. Wallpaper had replaced decorative veneer plywood as a surface finish for walls. It wasn’t that decorative veneer panels were no longer available for walls, but rather that the housebuilders stopped using them because they were expensive. So wood came to be used only for floors. That leaves us with the problem that it is really difficult to respond to color trends like dark or bright just by varying tree species, for example to provide matching colors by using a special type of teak or walnut.

I was chewed out by the president, but when I insisted that a certain machine was absolutely necessary, the company’s managing director said "Nakajima, go ahead and buy it," and I was able to introduce the equipment to the factory. This enabled us to make products in a variety of colors while preserving the characteristics of the decorative tree species used as surface material. Next we had to sell those products. When I asked that our colored flooring be sold through the normal sales channels since they would become the mainstream from then on, dealers said, "Do you really think this is going to sell?" But I kept on pushing them, and even got into a fight over it.

Our color flooring was launched in 1980. It was rough going at first. But once major homebuilders started using it in their model rooms at housing parks, people started talking about it. Orders from customers started coming in when carpenters [lead contractors on local housing starts] began to pay attention. Then, the products started to move even through normal sales channels, and they became widely used. The housing parks where homemakers construct their model homes served as important venues for spreading the new idea to the general public.

Color Floor

Housing parks came on the scene in the early 1960s. Do you think it makes a big difference to show actual spaces, to show products within a space?

Local carpenters bring customers to housing parks. I’m talking about customers who contract directly with a carpenter to build their house, and have nothing to do with the major homemakers. At the housing park, you can hear people saying things like, "Let’s do it like this example," or "Hmm, I’d like the same as that one over there." We also have a showroom for presenting our products, but we can’t show you a whole house, or how a product looks installed in a full-size space. Model homes in housing parks have enormous persuasive power.

Veneer thickness

Changing the topic, it seems that depending on the thickness of the veneer, the human eye can determine whether there is a plywood base underneath or not. In other words, it’s possible to discern whether a decorative material is solid wood or veneer. I asked Kyoto University’s Wood Research Institute to investigate this question. What we understand from the institute’s data is that if the veneer is at least 0.3mm thick, it is impossible to distinguish between solid wood and veneer, but if the veneer is thinner than that, people can tell that it is veneer attached to plywood. There is some variation depending on the tree species, but based on these findings, Asahi has been advising its customers that it is not a good idea to use veneer that is less than 0.3mm thick.

Types of wooden flooring for residential use

A long time ago, I wrote a summary of the "History and Future of Wooden Flooring for Residential Use."

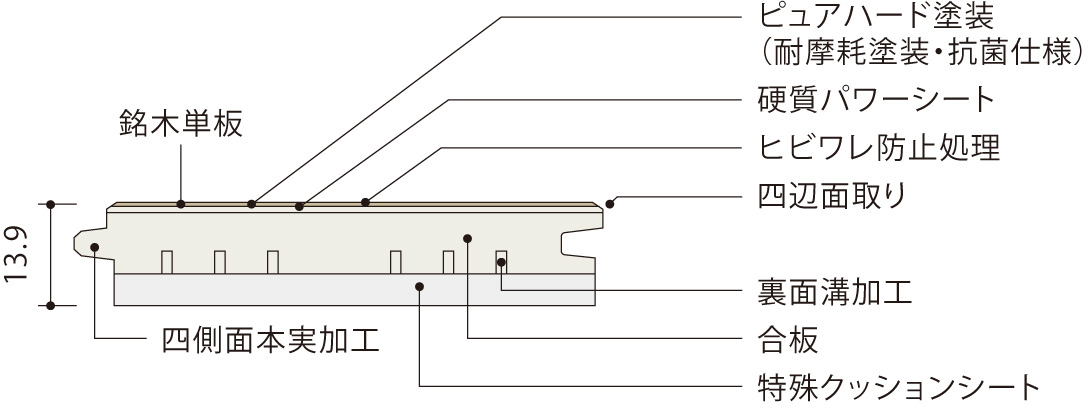

There are three types of wooden flooring materials for detached houses: flooring for use with sleepers and joists, flooring for gluing onto a subfloor, and flooring for use with underfloor heating. There are four types of wooden flooring for apartments and condominiums: flooring for attaching to a subfloor, flooring for gluing directly onto autoclaved lightweight concrete (ALC) or mortar, soundproof flooring, and flooring for both soundproofing and underfloor heating.The types can be further divided by the kind of material used: wood veneer or printed material as the decorative surface material, and plywood or laminated veneer lumber (LVL) as the base material. There are three types of wooden flooring materials for detached houses: flooring for use with sleepers and joists, flooring for gluing onto a subfloor, and flooring for use with underfloor heating. There are four types of wooden flooring for apartments and condominiums: flooring for attaching to a subfloor, flooring for gluing directly onto autoclaved lightweight concrete (ALC) or mortar, soundproof flooring, and flooring for both soundproofing and underfloor heating. The types can be further divided by the kind of material used: wood veneer or printed material as the decorative surface material, and plywood or laminated veneer lumber (LVL) as the base material. This array of flooring materials, combined with required qualities and performance such as dry cracking prevention and wear resistance, makes up the menu of available flooring products.

Plywood flooring structure | Cross section of a soundproof floor

Competition with printed flooring

In terms of sales volume, printed flooring is larger. But a market is never monolithic.

In the old days, "printed flooring" just meant flooring to which color had been applied by means of a rotary press, but since then various technologies have been developed and put into use, such as embossing to provide a textured effect corresponding with the printed grain and xylem tissue. I think these developments reflect a history of technological innovations by printing companies.

Printed flooring is uniform, so it’s easier to control its quality compared to veneer flooring, isn’t it?

It’s certainly true that printed flooring is easier than veneer flooring when it comes to quality control. But when we look at recent trends, we see that there are some customers who are reluctant to buy products that are too uniform or too perfect. They are looking for things that are closer to nature. Therefore, we notice recent trends in Asahi flooring such as demand for floorboards with knots, which in the past we used to discard as defective. The needs of the market change, so we have to do a good job of staying on top of those changes, or we won’t be able to release products that are ahead of the game or that can survive over time.

Could we say that the design of building materials has been driven by the building material manufacturers and their technological advances, rather than by the homebuilders?

Rather than say it’s one or the other, I would say that there are people who work for major homebuilders who think about home interiors and have a clear "view" of what they want. So far, they have been the ones who have created the market, and I think they will continue to create it. What distinguishes the most reliable major homebuilders from the others is probably the presence of such opinion leaders. But even when a company has people like that, there’s a risk that the corporate structure will squash them. It’s important to have a system that can translate those opinions into actions.

Of course, Asahi Special Plywood (Woodtec) has a long history of developing new designs in-house and releasing new products. In fact, the company is still doing that today. But it’s very difficult to get the homebuilders to buy new offerings. They always say the new stuff is too expensive!

So, is it fair to say that homebuilders took the lead in design development during the color floor period from the 1980s to the 2000s, but after that, building material makers have been leading the development of high-end products that respond to the preference for natural wood materials?

Yes. But, of course, the ability to lead development varies from company to company.

And within a company, the relationship between sales and engineering is also important. If the sales staff tell you, "Don’t make stuff like that and expect us to sell it!" there’s not much you can do. So, when I was still working, I would pair up an engineer working on product development with someone handling sales and send them together to visit building contractors and materials dealers. It’s not good enough for the development engineer to hear second-hand from the salesperson what the dealer is saying. It’s all too easy to end up with just a summary of what the dealer says, maybe in one word, like "expensive." When the engineer and the sales specialist go around together, they do a proper job of collecting detailed information. The way I saw it, if we couldn’t get this kind of information, we couldn’t create new products.

So rather than making inquiries of dealers, is it more an attitude of listening to their opinions and being prepared to discuss and persuade? When you spoke earlier about the 0.3 mm thickness of the veneer, it seems you went properly prepared with data to make a convincing case. Have there been significant changes to the customer base since you developed colored flooring?

The focus has shifted to the residential market. It’s not only homemakers, but it’s almost all residential, including the major homebuilders. Exports are close to zero. The company probably no longer produces the kind of wall materials that it used to make.

Basic approach to product development

One way that I look at it is that market needs change in an upward-moving spiral around a single axis. Long ago there was a time when flooring was popular, and they say we’ve come back to a time when flooring is popular again. The spiral has gone full circle. In my view, the new era of flooring that we have returned to is still centered around the axis, but it is on a higher level than the old flooring era. So instead of thinking that wooden flooring has returned to the market, you should think that the market is seeking a different kind of wooden flooring. It’s important to have your basic thinking about development oriented in this way.

The same was true when we were asked to develop flooring materials to use with underfloor heating. After Color Floor had become established, next was wooden flooring that can be used with radiant floor heating. They are both wooden flooring products, but they are not the same thing. So, design is one aspect, but if you don’t venture into adding functionality like floor heating or acoustic insulation, you haven’t told the whole story about flooring materials.

Asahi’s business has consistently aimed to bring precious wood to the mass market. Along the way, times have changed, the market has changed, and your products have changed. Is there a difference between aiming for the mass market and following changes in the public’s values?

Yes, they’re different.

Nowadays printed products have ended up overtaking wood. When wood grain prints first appeared, manufacturers were making products that imitated wood grain. You could call it fake wood grain. But the wood grain patterns that printing companies are making today do not exist in nature. Yet, even though they are not natural, ordinary people simply see them as wood patterns and find them beautiful. These are original designs—they’ve actually been designed. Asahi Woodtec was always committed to veneer, but after I retired, the big homebuilders began to use plywood flooring decorated with printed sheets of olefin, and there was increasing interest within the company, so Asahi’s plywood flooring range now includes olefin sheet products.

Still, what makes Asahi Woodtec stand out is the company’s continued commitment to wood. That spirit has been passed on, and I feel like the market’s preference for natural things is growing stronger. Instead of 0.3mm veneer products, the next generation of employees has developed products that use 2mm thick sawn boards, and sales are strong. Bringing precious wood to the masses may no longer be a matter of making it cheap. It’s about adapting to the needs of the market.

Interviewers: Nakamura Takayuki, Life Style Laboratory, and Ueki Keiko, Planning Office, Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka

Interview editor: Keiko Ueki | Photos courtesy of Asahi Woodtec Co., Ltd.

* This interview was conducted in 2017.

This Designer Testimony series presents digests on specific themes from the oral histories being recorded for the Industrial Design Archives Project (IDAP). IDAP plans to publish its oral histories in detail in reports and other formats.