Industrial Design Archives Project

Industrial Design Archives Project

Designer Testimony 02

A professional at making the intangible

—Designing relationships

Tatsumi Masakazu

Born in Kyoto in 1936, Tatsumi Masakazu graduated from Kyoto Institute of Technology’s Department of Design in 1961 and went to work for Riken Optical Industries, Ltd., a precursor of today’s Ricoh Company, Ltd. In 1964 he moved to Matsushita Electric Industrial Co., Ltd., where he worked in the Corporate Design Department headed by Mano Yoshikazu. In addition to designing all types of individual products, he was active in the improvement of living spaces and in the design of new units and systems, which was a new idea at the time. From 1978, Tatsumi headed the Design Office of the Design Department in Matsushita’s Home Appliances Division, and in 1987 he was appointed general manager of the Home Appliances Division Design Department. While working for the Home Appliances Division, he worked on the development of the LaunDream fully automatic home laundry system and the BEGIN series, which targeted women living alone. After his retirement, from 1993 to 2001 Tatsumi served as managing director and then secretary-general of the Japan Design Foundation, and worked toward holding the International Design Festival in Osaka. He has received numerous awards, from Matsushita Electric and from outside the company, and has published many papers on design and product development.

No one can fully appreciate the enormous impact that the introduction of electricity had on life in Japan after World War II. And it was home appliances that converted the power of electricity into "convenience" and "comfort" delivered to our homes. Suddenly, people no longer had to rub dirty laundry on a washboard or have to think about adjusting the heat under a rice pot anymore, because home appliances automatically washed our laundry and cooked our rice.

According to Tatsumi Masakazu, who created numerous hit product series while working for Matsushita Electric Industrial, "The story of automation is the story of the human ego." For 30 years, Tatsumi closely followed the needs of that human ego as he worked on the front lines of home appliance product development. And, since the 1970s, he has also addressed issues related to design ethics from the standpoints of energy and conservation of the environment.

In this second installment of IDAP’s "Designer Testimony" series, Mr. Tatsumi talks about how the development of home appliances led him to think about people, things, and the relationships between them, and from there to think about systems, spaces, and environments. Rather than designing "things," Mr. Tatsumi sees his job as designing lifestyles, consisting of a series of varied events.

How did you come to embark on a career in industrial design?

In elementary and junior high school, I dreamed of being a novelist or a manga artist. After I got into high school, I started wanting to be an architect, but I spent all my time on the newspaper club and I guess I had a little too much fun during my high school days. So I couldn’t get into Kyoto University’s architecture program. But the following year I checked into it and it turned out that Kyoto University was not the only place that taught architecture; there was also an architecture department at KIT (the Kyoto Institute of Technology) and not only that, there was even an Industrial Design and Industrial Arts Department there. I figured since the word “design” was in the department name, it must be something to do with design. I didn’t know what an industrial designer would do, but I was drawn by the word “design.” So I took the entrance exam for Industrial Design and Industrial Arts.

Since there was no newspaper club at KIT, I joined the drama club. Along with five classmates from Industrial Design and Industrial Arts, we all came into the club at once. When architecture and design students show their talent in theater, they don’t do it by acting, but by making stage sets, props, and costumes. While we were working on those things, each day just flew by.

Since that’s how I spent all my time, once again I neglected my studies! The way job hunting worked in those days was a student would do an internship at a company during summer vacation of the fourth year. After that there would be an interview where the student would get an unofficial job offer. Internship assignments were decided according to the order of each student’s grades in the first three years of study. Since I was around the middle of the heap, by the time my turn came around the only place left that seemed to me that it might be interesting was Ricoh (then called Riken Optical Industries), which made cameras and copy machines. That’s how I ended up going to work for Ricoh.

Why did you move from Ricoh to Matsushita Electric Industrial?

Ricoh is in Tokyo. Tokyo is a fine place, but I thought there’s no way I could live in Tokyo my whole life. Another reason was that while I was at Ricoh I participated in contests and things like that, and I got the feeling that electric appliance design would be a good fit for me.

At Matsushita, your first assignment was the Corporate Design Department?

In the Corporate Design Department, we received requests from divisions that either never had any designers, or had designers but they needed support. My first job was for the Bicycle Division, designing bicycle cargo racks and parts. After that, I worked at the head office for about 12 years, but since I was in charge of development, I was able to work as much as I wanted with a variety of business divisions. I think what’s most important in product development is maintaining the perspective of an amateur, along with the sense of tension that results when an amateur clashes with an expert. For example, there’s the time I got sent from the Corporate Design Department to help out product developers in the Vacuum Cleaner Division. The Vacuum Cleaner Division has its own designers who work for the Vacuum Cleaner Division. They are pros when it comes to vacuum cleaner design. They’re probably thinking, "What do those guys from the head office know about vacuum cleaners?" That kind of expert and a designer from the Corporate Design Department—who’s an amateur—should never compete head to head in the same domain. What the amateur needs to do is dig in and ask, "Why?"— "Why did you make it like this? Why are the wheels here? Why? Why?" Then the expert realizes that actually he doesn’t have the answer, and has to say, "I don’t know why. It was like this in the previous drawing." Before we start producing a product, we have to make sure that we have thoroughly discussed these kinds of things. By working with all kinds of business divisions, I learned about the great power of the company as a whole, I came to know the power of "All Matsushita." Even if each business division was happy by itself, they didn’t combine their strengths enough. But when we did combine forces, we were awesome.

Can you give a specific example of the importance of joining forces?

The first example would be the educational equipment project (1974–1977). This was a request from the Special Equipment Sales Division. They said they were losing to Sony in the field of educational equipment. Matsushita Communication was already making so many products that it had a catalog. When they asked if we had any good ideas, I thought of design integration. The target market was schools. Specifically, audiovisual classrooms, broadcasting rooms, language labs, etc. Therefore, we designed the overall space by making standard units and systematizing our products. To make it easier to do business, we even made models that the sales people could put in the trunks of their cars and take to the schools. In addition, we participated in many unit or system-based projects in collaboration with multiple business divisions or Matsushita Group companies. For example, we exhibited "capsule housing" at the Inter-Living Show (1971) and developed units for Lions Mansion condominiums (1971–73). Once in a while I called in at the Sales Division when requested to explain something at a gathering, and as long as I worked at the head office, I always kept in touch with the people there. After all, I’m a former drama club member and an Osaka dialect speaker, and I like to be the center of attention! Anyway, I decided to devote 70 to 80% of my energy to my work for the company. I put the other 20% into other work. I’ve done whatever I could, whether it’s JIDA (Japan Industrial Designers Association) activities or part-time lecturing at Kyogei (Kyoto City University of Arts).

A capsule housing room

A capsule housing room

Was it that kind of attitude that led you to taking on company-wide projects?

The "New Family Project" (1975–77) was undertaken by All Matsushita, the entire Matsushita Electric Group. This was a major undertaking. The Design Center (formerly the Design Department) heard about it from the General Planning Office. It all started because the head of the General Planning Office at that time wasn’t somebody who just cared about numbers, but rather felt like we should do something to make people sit up and take notice. The Sales Division and the Advertising Division joined the General Planning Office and the Design Center in forming a committee. The business units were organized into three groups according to their product categories. Each one sent a representative and a working group was formed, with the vice president at the top and the Design Center director, Mano Yoshikazu, and the general manager of the General Planning Office responsible for steering the group. The group worked on company-wide development proposals based on the idea of a "new family." I was in charge of setting up the organization for this project, including serving as its secretary. I was able to do the job because I had spent 10 years building a network within the head office, and I had gained people’s trust. Maybe you could call my role that of a producer. I guess I had come to understand the thoughts and perspectives of the organization and its leaders. Another big factor was that the Corporate Design Center had grown strong enough to tell the business divisions’ design departments what to do.

In 1976, the number of Japanese born after World War II grew to exceed half of the total population. Members of this postwar generation were different from previous generations in their behaviors and values, and they were creating new lifestyles. This was an important issue when it came to developing new markets, and we had to take a company-wide approach in our thinking about product development and design, and sales promotion. There were proposals from each business division, and the committee examined them and decided what to present at exhibitions.

You served as the group’s secretary, right?

The business divisions’ proposals were based on what they wanted to do from the start, without considering the company-wide project. The secretariat helps them tweak their proposals in order to gain the understanding of top management, by advising them on things like what the Sales Division has to say, and what kind of technical strengths they can make use of. We help them make their proposals easier to understand. Then if a proposal matches the "new family" concept, we could push it. It’s important to do a good job of selling to people inside the company. In a certain sense, design departments are not accountable. If you try to be accountable for every little thing, you can’t make any proposal. So it’s true that, in a sense, proposals are a designer’s job. If you don’t make a proposal, nobody will understand what you are trying to do.

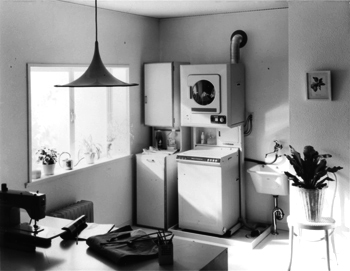

This Designer Testimony focuses on the first half of Tatsumi’s career. Later, he moved to Matsushita’s Home Appliances Division where he and his colleagues constructed a manufacturing environment based on lifestyle research (comprehensive research and analysis of consumer awareness, values, feelings, needs, and living patterns) and launched hit products like LaunDream and Canister. I wanted to discover where he found the energy needed for so much activity. This led me to think about what is demanded of designers even more than sharp senses and reliable skills. Tatsumi emphasizes "persuasion." And that is why his favorite saying is always, "Number one is forbearance, number two is guts, there is no number three or four, and number five is good taste."

National LaunDream home laundry system

National LaunDream home laundry system

Interviewer/editor: Keiko Ueki, Nakanoshima Museum of Art Osaka Planning Office

This Designer Testimony series presents digests on specific themes from the oral histories being recorded for the Industrial Design Archives Project (IDAP). IDAP plans to publish its oral histories in detail in reports and other formats.