Industrial Design Archives Project

Industrial Design Archives Project

Designer Testimony 05

Design management distribution and integration

Sakashita Kiyoshi

Born in the Senba area of Osaka in 1933, Sakashita Kiyoshi took the design course at Osaka City Kogei High School, graduating in 1952. He went on to Tokyo University of the Arts, graduating from the Department of Design in 1957, and joined Hayakawa Electric (now Sharp Corporation) the same year. After working in the No.1 Engineering Department (radios) and the Appliances Division, in 1963 he was assigned to Sharp’s sales company in the United States. Then, in 1966, after working in the Head Office Industrial Design Department, he moved to the Audio Systems Department. He put a great deal of effort into establishing the Corporate Design Center in 1973, and was appointed the first director of the Center. In 1981 he joined the company board as Corporate Director and Group General Manager of the Corporate Design Group, and in 1989 became Executive Director, retaining his responsibility as Group General Manager of the Corporate Design Group. On reaching retirement age for board directors in 1995, he was appointed a corporate adviser, and became a director of the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design (ICSID). From 1996, he lectured at Kobe Design University, Ritsumeikan University, and Musashino Art University. He retired from Sharp in 1997, and in 1999 as a full professor, became head of the new Department of Informatics at Musashino Art University, retaining the post until 2003. From 2000 to 2010, he was chairman of the Osaka Design Center. Today, he continues to contribute a column to the Osaka Design Center website, writing on humanity and design.

After losing his machining plant in the massive earthquake that struck the Tokyo area in 1923, Hayakawa Tokuji was forced to sell off the mechanical pencil business and start afresh in Osaka. His new business, eventually to be called Sharp, continued to be innovative, producing many firsts. The first radio and TV sets produced in Japan were made by Hayakawa Electric, as were Japan’s first mass-produced microwave oven and Japan’s first electronic desktop calculator. And in addition to the “sharp pencil,” Sharp’s innovation provided the Japanese language with another new word: the everyday word for the sound of a microwave (“chin”) is derived from the “ding” of a bicycle bell incorporated into Sharp’s 1967 microwave oven to announce that cooking was done.

Sakashita Kiyoshi was attracted to Hayakawa Electric by its enthusiasm for skilled manufacturing and its entrepreneurial spirit. Having joined the company, in addition to working directly on design, he put a lot of effort into organizing a design division, eventually becoming a director on the board of the main company, an unusual progression for a professional designer. He continued to lead design at Sharp until his eventual retirement. In this interview, he talks about some of that history.

Note 1: Launched as the Hayakawa Mechanical Pencil. An improved version was rebranded the Ever-Ready Sharp Pencil.

From Osaka City Kogei High School to Tokyo University of the Arts

I was born in Osaka, in the Senba area. It was close to the Honmachi district where there were a lot of textile wholesale merchants like Marubeni and Itochu, so I frequently saw people working on products with colorful labels, packaging them for export. When I was in about the sixth grade, children were evacuated, and my group was sent to a mountainous region in Shiga Prefecture. I briefly returned home later to prepare for my graduation ceremony, but the timing was bad, and there was a massive air raid the night I arrived back in Osaka. Everything burned down, and I was left with only the clothes that I was wearing. My health deteriorated, and I had to take a whole year off school. The war came to an end, and one of my clear memories from that period is of seeing an American Jeep on the Midosuji Avenue—the simple and powerful design left a deep impression, which probably had a substantial influence on my thinking in later years.

Ever since I was small, I had been good with my hands, and I seemed to have a talent for drawing, so my father apparently asked a nearby textile dyer about career directions. I was family’s second son, so taking over the family business was not my destiny. The dyer told him about the Kogei High School (Note 2). I have no clear recollection of whether I personally was interested in taking that route, but the result was that I started on the Kogei High School’s design course. The education system was being restructured at that time, and the others on the course had all studied drawing and painting at three-year junior high schools, which meant that they could paint proficiently in poster colors. I had no such grounding at all, so I had to put in a lot of hard work in order to catch up. Many of my contemporaries were aiming for careers in poster design or graphic design, and were keen to get into the advertising departments of department stores like Daimaru, Hankyu or Kintetsu. I, on the other hand, had no intention of finding work after graduating from Kogei High School, so I wanted to go on to a higher school. I applied for Geidai (Note 3), but I was completely unprepared, and was quickly rejected. I hadn’t even realized that academic ability accounted for half the entrance exam. After high school, I went to study in a sketching class at the Fine Arts Painting School (Note 4) which was located in a basement in Tennoji. That was in the mornings. In the afternoons I studied at a prep school. After half a year studying like that, I moved to Tokyo and found lodgings so that I could attend a prep school specializing in sketching. At the Painting School in Tennoji, the teacher had often criticized my drawings, saying that my technical skills were good, but the drawings had no soul. I explained that I was trying to get into a design department, and he said “Is that so? Well, in that case it doesn’t matter!”

The year of preparation paid off, and I was able to get into Geidai’s Department of Design. In fact, it paid off so well that I had been the top-scoring entrant, and was designated class president. “You had the top marks, so you get the job,” I was told. There was no organized specialization within the Department of Design, but only four students in the class of thirty were aiming for careers in industrial design. Companies didn’t even have departments dedicated to industrial design in those days. The Geidai department was hardly focused on industrial design, but Ekuan Kenji was one or two years above me, and Koike Iwataro was teaching there. It was the time when he was doing work such as furniture and other designs for Yamaha. Professor Koike gathered together a group of students including Ekuan, and they started to collaborate on design projects. They called the group GK, with the G standing for Geidai and the K standing for Koike. With things like that going on, I found the environment very stimulating.

Note 2: Osaka City Kogei High School

Note 3: Tokyo University of the Arts, often known as “Geidai”

Note 4: The Fine Arts Painting School was a public sector institute established in 1946 as a vocational school for studying practical skills in the fine arts, and was co-located with the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts.

Return to Osaka: Starting at Hayakawa Electric

Because of my Osaka roots, I felt drawn toward Osaka companies. But Matsushita Electric and Sanyo had already taken on graduates from Geidai, and I didn’t want to go to a place where everything was already set up. I found Hayakawa Electric was attractive because I knew that its founder, Hayakawa Tokuji, was a one-of-a-kind business leader who was fervently keen on skilled manufacturing, and that he also placed importance on creative aspects. I was already familiar with the company because, when I was at Kogei High School, we often went to Hayakawa on training sessions or factory visits where we could see manufacturing in action. The company’s design division was still very small, but when I saw its recruitment notice—I think it was posted in the university office—I applied, and Hayakawa Electric took me on. That was in 1957.

My first posting was the industrial design section of Hayakawa’s No.1 Engineering Department. At the time, it wasn’t called the industrial design section; it was simply Section No. 4. There were already a number of Kogei High School graduates there. The Kogei High School program was not designated as being for industrial design, but Chiba University professor Yamaguchi Masaki had brought in Bauhaus thinking. In practice, the school had been providing industrial design-like education. I was Hayakawa’s first hire from a university level design course, so I was put to work on design as soon as I joined the company. I began with radios. TVs were handled by the No. 2 Engineering Department.

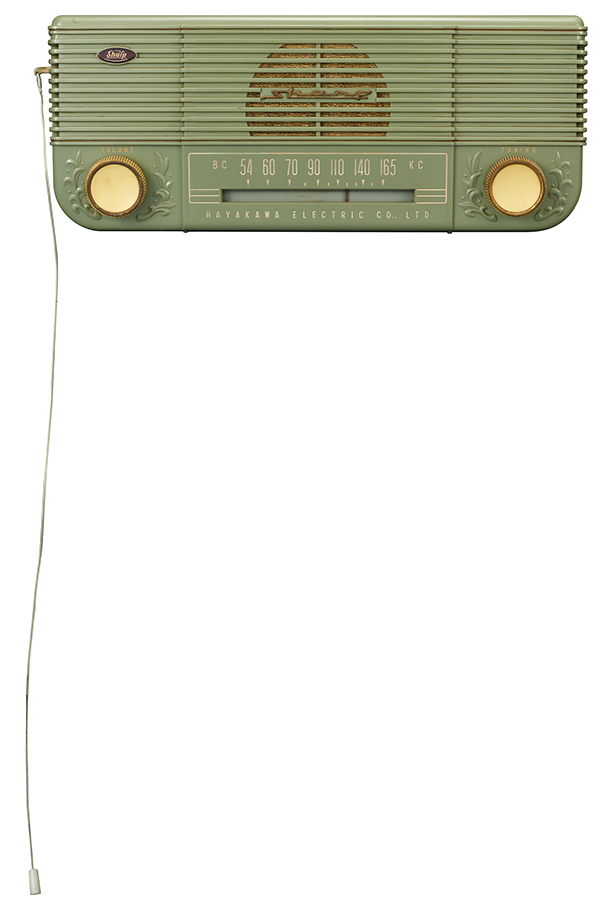

Timing-wise, this was in the early days of transistor radios. There was no division charged with product planning, so the engineers and the designers worked together directly. For the Five Tube Super wireless receiver, I was given a chassis with five vacuum tubes on it, and my job was to take the design from there. In effect, I was dressing the product. Today, product designs begin by aligning with user needs, but in those days, the designer was responsible for the design of the exterior.

Appliances Division: Substantial responsibility, effective immediately

The company president’s enthusiasm for skilled manufacturing meant that the monthly new product planning meeting often extended late at night. At the time, I was only a rank-and-file employee, so I didn’t take part in the meeting itself, but I keenly listened to the conclusions the following morning, and was relieved when I heard that my proposals had been accepted. Occasionally I was called to the president’s office to receive instructions directly. I was still only in my second year at the company when I was transferred to the new Appliances Division, which was developing white goods from scratch, beginning with electric refrigerators, and then moving on to washing machines. Hayakawa had started with radios, so it was lagging behind other manufacturers in the area of white goods (large electrical appliances for the home). It had been decided to construct a new domestic appliances factory in Yao, and to establish the Appliances Division. I was appointed as the Engineering Department’s chief designer, accompanied by one more designer from another department and three new employees to make a five-person team charged with all aspects of design in the new division. There were no existing designs to build on, so we were effectively given carte blanche. There was a vast amount to be done, and we were incredibly busy, but being allowed to take the overall lead was really good for me. When our designs turned into actual products and were shipped to retailers around Japan, the sales figures and the like provided immediate, tangible feedback on our work. That was one of the things that made the work very satisfying. And when it was time for the monthly product planning meetings at head office, my boss, the head of the Engineering Department would say, “I can’t talk about the design, so you need to come along too.” Consequently, although I was little more than a fresher, I was called upon to stand up and explain the design in front of the company president. Being given that sort of responsibility when I was so young, and managing to somehow make a success of it, was a great experience that was extremely useful to me when working in management in later years.

I remember one occasion when I stood up to the president. We had a design for a room fan with a beautiful circular stand. To make sure that the fan did not tip over, the base was set forward, leaving a large space in front of the pedestal. We used that space for the control switches. The president had started his career by making decorative metalwork in a traditional working-class area of Tokyo, and he had kept his own ideas and opinions on design. One of the company’s hit products at that time was a wall-mounted plastic radio that had been designed with scrollwork around the knobs in accordance with his instructions. Looking at the fan design, he said to me, gently, “There’s some space around those control knobs. How about adding some scrollwork?” I blew up, saying “No way! It’s deliberately simple. That’s what gives the design its balance. There’s no way I can put decorations there.” The mood in the room suddenly changed. Saeki Akira—who was managing director at the time and later took over from Hayakawa as president—stepped in to rescue me, but afterward I was given a thorough dressing down for going against the president like that, especially as I was still new to the company. As a result of that incident, the president remembered me well, and would occasionally send for me in order to ask me questions or seek advice. So, not knuckling under may not have been so bad after all.

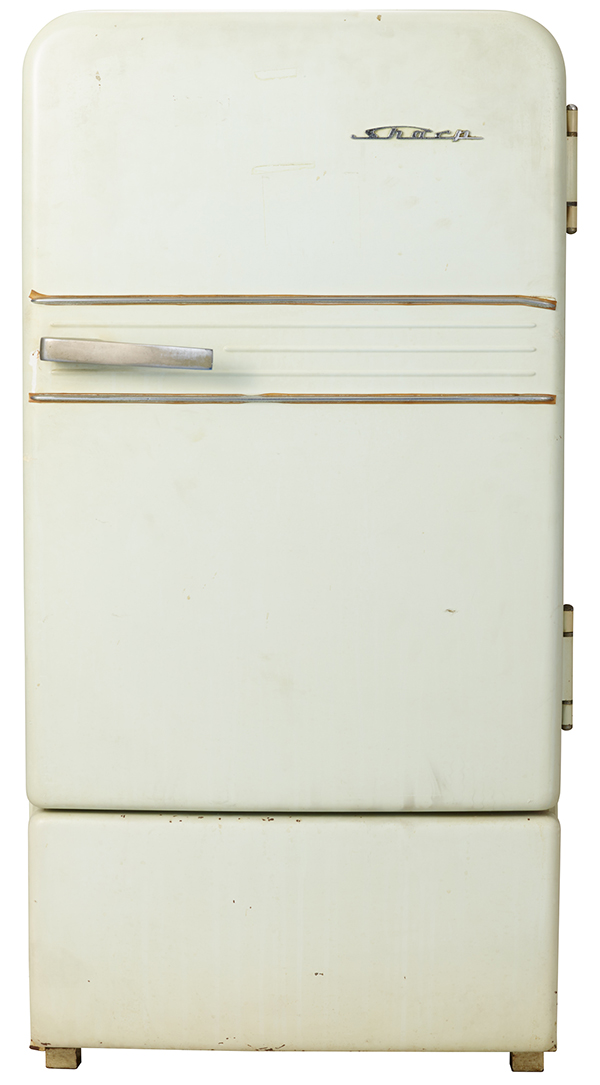

HR-330 refrigerator (1958)

5M77 Five Tube Mini Super radio (1956)

Working on side projects and outside activities from early days

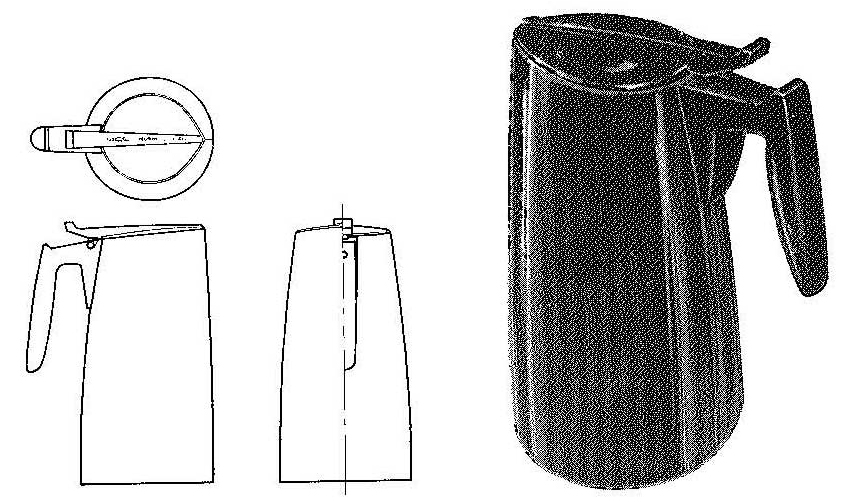

At that time, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) was putting a lot of effort into promoting design. MITI organized a design concours for general merchandise, and as part of the competition, National Vacuum Bottle in Sakai (Note 5) solicited ideas for a tabletop vacuum flask. I had only just started at Hayakawa Electric, but seeing that the project was for a type of design that was somewhat different from those made by the company, I decided to have a go. I entered the concours and happened to be selected as one of the winners. In those days, vacuum flasks were mostly housed in cylinders made of tin plate, like the sorts of tins used for Japanese green tea. I was able to use my experience of molding plastic casings for radios to produce a simpler housing for the flask. That was my entry. Winning ideas rarely made it to the market, but the president of National Vacuum Bottle wanted to commercialize my proposal, so I went to Sakai to help by producing the design drawings at weekends when I didn’t need to go in to work at Hayakawa. As a result, I became involved in new product development at National Vacuum Bottle as well as at Hayakawa Electric.

Note 5: National Vacuum Bottle Co., Ltd.

First General Merchandise and Ceramic Export Product Design Concours

MITI Light Industries Bureau Chief’s Award

National Everest Jack (1957)

(Published in Industrial Art News Vol. 25-11)

The first floral pattern appliance

One day, I was at National Vacuum Bottle, talking about the work, when the president of a printing company that specialized in printing on tin plate came to talk about the new American full color high-speed sheet metal printing machine that he had just installed. He was keen for us to think of some new designs to use it. That gave me a flash of inspiration. Everyday life in America and Europe was full of floral patterns, and Japan had just switched over from semi-outdoor kitchen areas to modern dining kitchens fully integrated with the living area. Dining tables had also changed. I reasoned that a printing machine like that could probably produce floral patterns suitable for decorating items to be placed on the dining table and in areas where the family relaxed together. One of my university contemporaries who had been studying textile dyeing design had taken a job at Marubeni, and I got him to introduce me to a Yuzen artist in Kyoto. The image of the fan-shaped template needed for applying a pattern to the body of a vacuum flask was very similar to that of templates for kimono fabric—like the hem or skirt pattern. The artist paints on the flattened template, imagining how it would look when applied to the skirt and worn. This inspiration led to an Everest vacuum bottle (Note 6) being the first domestic appliance in Japan to have a floral pattern. Other manufacturers soon copied the idea, which spread from vacuum bottles to table-top water heaters and then to many other products.

Note 6: “Everest” was one of National Vacuum Bottle’s product brands

To America

In recognition of the business results at the Appliances Division, I was promoted to Section Chief at the age of twenty-seven. The room fan designs were very popular in the market, and we launched the industry’s first smoke-free tabletop fish roaster and the first kerosene stove produced by an electric appliance manufacturer. Hayakawa Electric became one of Japan’s top manufacturers. Everything was going smoothly. Then, at the end of 1963, the year when President Kennedy was assassinated, I was called in by our managing director Saeki Akira. I didn’t know why and I felt somewhat apprehensive as I went to see him.

In the spring of that year, Hayakawa Electric had established a local sales company in the U.S.A., mainly selling transistor radios. Before long, the people working there asked for a designer to be sent over. “The market is very different. We’re not going to succeed here just by watching others and following their examples. We need a designer.” “Off you go,” was the order I received. A week later, I had gathered my stuff together and was on the plane. Moreover, I had been told to take my family with me. In those days, most people posted overseas went alone at first, but Saeki said that getting a feel for the lifestyle and the kitchens was important, so he recommended that we went as a family. My child was only one or two years old at the time, so my wife had to navigate a lot of difficulties. That year, the first DC8 jets had started flying the routes, and the exchange rate was 360 yen to the dollar, or effectively 400 yen to the dollar. The sales company was based in New York, but before we could get there we had to refuel in Hawaii, and then take a break in Los Angeles. It was not an easy trip.

Transistor radios were a product unique to Japan. America was still in the age of home radios with wood cabinets. That made our job relatively easy. All we had to do was create a new market for the new technology from Japan. At the start we had some fairly colorful products, but before long, black and silver emerged as the standard design for compact radios. The problem we faced was that America was so big. There were lots of things that could not be understood just by looking at the market in New York. Moreover, there was no easy way to send information about different regions in those days. Just taking photographs, developing and airmailing them, plus writing and sending weekly reports, took up nearly all of our time. There was so much that we were encountering for the first time. Matsushita Electric and Sanyo had also set up operations in America, but Hayakawa was probably the only one to have sent a designer, and people were often surprised to hear what I was doing. Apart from sales teams, most of the people sent over were engineers. But it was clear to me that working together with the sales people made a big difference. You get the opportunity to hear the voices of the people who actually use the products. There was a lot I had to learn. Including the language!

Back to Japan. To a much larger company.

After a little over three years in America, I was brought back to Japan and assigned to the Industrial Design Department in the Central Research Laboratories. I was attempting to give the company’s designs a consistent image, but I ran into a lot of difficulties. But before long I was pulled out of the situation by the newly established Audio Business Division, and set to work on the development and design of stereos, radiocassette players, tape recorders, and similar products. Exports accounted for 80% of sales, and I got roped into negotiations with buyers or called up to act as an interpreter! Boy, was I busy.

The major electrical manufacturers in the Kanto area around Tokyo—Toshiba, Hitachi, and Mitsubishi—were all big businesses in pre-war times, and they had operating units all over the place. That made it necessary for those companies to place their design departments at head office. In contrast, Sharp had grown rapidly, sending designers out to each of the business divisions. Audio products were designed in Hiroshima, TV’s in Tochigi, calculators in Nara, and so on. Nevertheless, some of the designers felt that they didn’t want design to be decided unilaterally at each of the business divisions, and several came to me and appealed for me to do something about it.

After that, the head of my business division told head office how bad the situation was, and I was called up to head office to explain. It turned out that the president had also been vaguely aware of the issue. He said “OK. I want you to make a business plan for head office. And include studying what we should do to set up a new design division,” ordering me back to head office. My first draft, ready after only one week, was titled “A unified design organization, both distributed and integrated,” which led to the current Design Division. The result was the Corporate Design Center, established in September 1973.

The essence of the idea was that product quality could only be achieved on site. For that reason, the designers need to be at the production sites. But the authority to control designs rests with the head of the Design Division. In other words, the decision on whether to produce a product needs to be taken by the head of the business division, but the decision on the design and decisions on appointment of designers need to be taken by the director of the Corporate Design Center, which was me. Proposing and implementing design strategies is a head office function, with only the minimum staff necessary. And in the Corporate Design Center we set up design centers corresponding to each of the business divisions: a TV Design Center, Audio Design Center, Appliances Design Center, et cetera. We also aimed to raise the proportion of female designers to 30%. The aim was to ensure that products reflected the needs of women, who were the predominant users of domestic appliances. The Corporate Design Center started with a staff of 70 and actively recruited, reaching 100 in 1976, but remained a “small government” for design.

New Life product strategy and chainstores

In the middle of the 1970s, the company started the New Life product strategy, based on an idea by the managing director. This was originally triggered by the emergence of energy efficient products to cope with the first oil crisis. All the manufacturers had launched products such as refrigerators with fewer shelves, smaller TVs, and compact washing machines, but consumer reaction was only lukewarm. One of the big hits at the time was a compact vacuum cleaner designed by one of the company’s female designers. The reason for its popularity was apparently its cuteness. This demonstrated that the motivation for product purchase was shifting from function to taste. Surveys investigating the details of the trend showed a new lifestyle had emerged and taken hold among baby boomers—people born in the postwar period—and that consumption determined by emotional considerations had taken a central role in the market. It was decided to concentrate on developing New Life products, with the product planning departments of each business division joining in. The aim was to leverage our manufacturing skills to produce products that differentiated us from other companies, taking a bright red refrigerator as an example. This provided an easy-to-operate environment for the company’s designers.

The new strategy was well timed. Up until that point, there had been some 35,000 electrical shops throughout the country. About 30% of those were affiliated with Matsushita Electric, which gave it a massive presence in the market. In contrast, only about 3,000 shops were affiliated with Sharp (Note 7). But at that time, large chainstores selling domestic appliances appeared, initially in the Akihabara area of Tokyo and the Nihonbashi area of Osaka, but expanding rapidly. The chainstores were happy to carry products by any manufacturer, as long as they were good products. Moreover, they would give the best products the best positions on their sales floors. That opened the way to sales of Sharp products through channels other than its affiliated electrical shops. We were rapidly launching new products, and our sales grew rapidly. This was a verification of the fact that design served to differentiate the products, raised their value, and contributed to corporate image. As a result, design-driven product development became standard practice.

Note 7: Hayakawa Electric changed its name to Sharp Corporation in 1970.

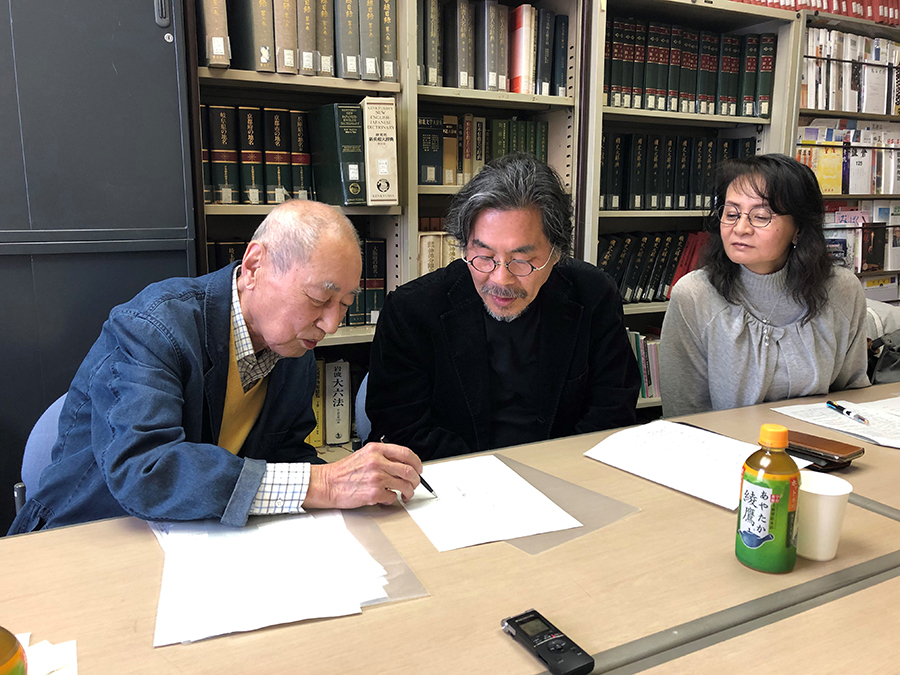

Sakashita Kiyoshi with retired Sharp designer Okuda Mitsukazu, and current Sharp designer Asai Yoshimi

Interviewer/editor: Keiko Ueki, Nakanoshima Museum of Art Osaka Planning Office

* Titles omitted in profiles, annotations, and supplementary explanations set in parentheses in interview articles

* This interview was conducted in 2019.

This Designer Testimony series presents digests on specific themes from the oral histories being recorded for the Industrial Design Archives Project (IDAP). IDAP plans to publish its oral histories in detail in reports and other formats.