Industrial Design Archives Project

Industrial Design Archives Project

Designer Testimony 04

Everything is in a process of change

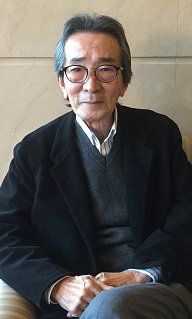

Naito Masatoshi

Born in Hamamatsu, Shizuoka Prefecture, in 1937, Naito Masatoshi graduated in 1960 from the Department of Arts in the Faculty of Education of Tokyo University of Education (now the University of Tsukuba), after which he joined Matsushita Electric Industrial Co., Ltd. (now Panasonic Corporation). He took his first steps there as a designer, working in the Industrial Design Section of the Home Appliances Division Planning Department. In 1972, he left the company to work in the family business, and in 1973 established the Naito Industrial Design Institute . He rejoined Matsushita Electric in 1974, and subsequently became Head of the Design Office in the Home Appliances Division Design Department, the Head of the Design Center Management Office, and the Head of the Design Department of the TV Division, before being appointed Head of the Corporate Design Center in 1988. Until his retirement in 1997, he not only led the management of the company’s design divisions, but was also active in a wide range of design-related organizations as part of his efforts to create an environment conducive to creativity for in-house designers.

In 1951, Matsushita Konosuke declared that "This is the design era," and Japan’s first Product Design Section (in-house design division) was established within Matsushita Electric. Mano Yoshikazu, who had been teaching in the Department of Industrial Design of Chiba University, was the first Head of Department, taking responsibility for design at Matsushita.

The history of industrial design in postwar Japan is often told as if it stems from this juncture in almost mythological fashion. It is as if Japanese industrial design not only started in that year, but its path was already completely laid out as a single straight line heading into the future. At its inception, however, the Matsushita Electric Product Design Section consisted of only a few staff. It is not hard to imagine that they had no idea of the path they should take, or even of the direction in which they were heading. Designing products is not the be-all and end-all of what it means to engage in design within a company. Our fourth Designer’s Testimony comes from Naito Masatoshi, who joined Matsushita Electric in the spring of 1960—the year in which Japan was rocked by protests against the US-Japan Security Treaty, and the World Design Conference, which asked "What Designers Can Contribute to the Human Environment of the Coming Age," was held in Japan for the first time—and was key to Matsushita’s design until the Kyoto Protocol was adopted in December 1997.

Studying design: Getting into Tokyo University of Education (now the University of Tsukuba)

It’s like a story out of a manga, so it’s not something to crow. The truth is that I knew almost nothing at all about design. I had no interest in it. I’d never painted a picture, or even drawn a proper line.

In high school, all I did was kendo. My high school had re-established a kendo club the moment the prohibition on kendo was lifted by GHQ, which meant it was stronger than its competitors, and when I was in my senior year I competed in the national high school championships. It was a big deal. The older students all rushed to tell me that "That’s the same as a baseball team making it all the way to Koshien!" As a third year, I was due to take university entrance exams, but I had no time at all to study, and the exams weren’t going to wait. Having been brought up in the sleepy town of Hamamatsu, I didn’t have any high aim in mind. Nor did my family have any money. So I decided that I had to go for a national university, and moreover for one of the top schools that all held their entrance exams on the same day in early March. I thought that would be cool. Normally, people who do that take exams in eight different subjects, but there was no way I had time to study for that many. Without any real justification, I thought I would do better if I could find somewhere that only needed five subjects. I did a lot of looking up! And the only place on the list that would let applicants take exams in just five subjects was the Department of Arts in the Faculty of Education of Tokyo University of Education. There was also a practical exam, but I didn’t know anything about that.

The practical exam was a shock. They told me to go outside and have a look around for five minutes, then when I came back I was told to draw the buildings I’d just seen. I had no idea what to do, so I just drew. I drew as if my life depended on it, like a preschooler. Then I happened to glance across at what the person next to me was drawing, and it was utterly different. It was so incredibly well done that I was stupefied. At the bottom of my heart, I was convinced that my application would be rejected. So I took the entrance exam to study economics at Doshisha University on the recommendation of my uncle, who was working in Kansai. But while I was there looking for a place to live, I heard that I’d got into Tokyo University of Education. I thought "That can’t be true. They must have got my marks wrong." My uncle told me to go to Doshisha anyway. "What sort of thing does that course involve? I know what architecture is, but what’s industrial design? Those people who paint the signboards outside stations—is it that?" he asked. I didn’t think it could be, but I didn’t know myself, either. I did know that the university was originally a teacher training college, so I would probably be able to become a teacher. More importantly, I wanted to go to Tokyo rather than Kyoto. That’s how I got into university, but it’s an unedifying story.

Fellow students

There were seven other students on my university course. To start with, I couldn’t hold a conversation with them. For example, they’d all be chatting about Le Corbusier. Until then, I’d never thought about design at all, and I had no idea what they were talking about.

At that time, most people’s idea of design was probably something like my uncle’s, but those people who had come to study it intentionally did actually know about it. Even the Japanese government had set up a design office in the Ministry of International Trade and Industry. Raymond Loewy’s Never Leave Well Enough Alone must have been translated into Japanese when I was in junior high or high school. So my seven fellow students knew far more than I did about design, and they were good at sketching and perspective drawing. Nevertheless, after studying for four years I did manage to graduate. I think I had the worst grades.

How did you end up joining Matsushita Electric?

In the summer vacation of my senior year at university, we had to do an industry placement. Lots of companies sent us placement offers. Almost all of them were from electrical manufacturers. One of my fellow students came from close to Lake Hamana, like me, and the two of us decided to do our placements at Matsushita after the professor pointed out that our homes were slightly closer to Kansai.

When we got home after finishing the placement, we received notifications that we could join the company, that we’d passed. The professor said that since they’d accepted us, why didn’t we go? So we both decided that we’d join Matsushita together. I had no objection to moving to Kansai.

Anyway, from high school to starting work, it was almost entirely one random stroke of luck after another.

Work after joining the company

When I joined the company in 1960, I started work in the Industrial Design Section of the Home Appliances Division Planning Department, that is, the section responsible for white goods. At the time, the Home Appliances Division was located in Toyonaka.

There were lots of business divisions for white goods. You know, there was the Washing Machine Division, the Iron Division, the Rice Cooker Division, the Heater Division. In the Industrial Design Section of the Division that pulled all these business divisions together, I was responsible for the Heater Division. But the Heater Division was at a site that was some distance away. Maybe that’s why they wanted a designer close at hand. So the Home Appliances Division sent four junior employees to work in that business division. It wasn’t until 1963 that I returned.

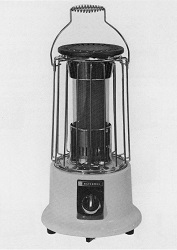

The GS3000 gas stove. That was one of your designs, wasn’t it?

It’s a design that lets you put a kettle on top of the stove. Gas stoves stayed this shape for a long time afterwards.

This was my pièce de résistance. It sold a lot better than I would have expected.

GS-3000

The gas stove that pioneered a basic shape that remained unchanged for a very long time.

This is a good example of the efficiency and overall robustness provided by an excellent design.

But then you left the company!

I’d been working there for 12 years. At the time I was responsible for designing white goods for export to the United States, and on a business trip over there I remember saying to my Head of Department "It’s time for me to quit."

My family ran a cotton textile business. My father had died in the war, but somehow the business was just about surviving. I was the oldest son. My uncle wanted me to take over from him, so I went home to Hamamatsu. But after doing it for a year, I hated it. The bolts of cotton were heavy, and the prospects were dim. So in the end I abandoned the family business and set up a design studio in Hamamatsu with my younger brother, who’d studied design at Musashino Art University. My uncle must have been aghast.

The Naito Industrial Design Institute

It was the first industrial design studio in Hamamatsu. We rented a single room in a tiny apartment block in the middle of some rice fields. We put in a phone line and desks and waited for customers, but of course they didn’t come. For one thing, most people were completely unaware of industrial design. In the end, via an intermediary who may have been a friend of my brother’s, we designed a rice dispenser, a box for quickly and smoothly dispensing a standard amount of rice . That was the start. Thanks to that, we gradually started to attract more customers, and the studio has now been going for 40 years.

But you yourself went back to Matsushita.

There was a Matsushita washing machine factory in Fukuroi on the other side of Hamamatsu. One day, I heard that a couple of Matsushita senior staff, Kikuchi Yutaka, who had been my boss, and Ogawa Morimasa, head of the Microwave Division, would be visiting the Fukuroi factory and that they wanted to see me. So we met in a hotel at Lake Hamana.

They confronted me, "You’re not doing what you said you would. When you quit, it was to take over the family business. But you’re working in design. If you’re working as a designer, you should be doing it for Matsushita." I’d quit because of personal circumstances, so had never imagined that anyone would say something like that. I thought back to the atmosphere we had when we were all working together. I suddenly realized I missed it, and wanted to go back to Matsushita. Thankfully, my uncle was astonished that such a benevolent company existed, and he gave me his backing. Of course, he already knew that I wasn’t of much use to him!

When you went back, it was to work in the corporate Head Office.

When I went back to Matsushita, I took it for granted that I’d be returning to the Home Appliances Division, but in fact I was assigned to the Head Office. I had no idea what I’d be doing, but this was just when the Industrial Design Department had become the Industrial Design Center (it was later to become the Corporate Design Center). So it turned out that I would be working in the Design Center under Mano Yoshikazu. Mano was the director, and the assistant director was Kurata Kazuyuki. Kurata was not a designer, but he had been involved in marketing. I became very fond of him, and he had a huge influence on me. That time became my own starting point.

What was the starting point?

Something Kurata said to me. "Do you know that at Head Office the design team talk about you as if you’re some sort of primitive?"

When I was in the Home Appliances Division, I was always in a good mood and enjoyed my work. That’s because things that I’d designed had been turned into products and were on sale in stores. Anyone would find that exciting! So I was animated in the office, too. I believed unquestioningly that my work was useful, and thought myself very lucky. Then came those words. They gave me a dreadful shock.

From then on, I became intensely aware of professional skill in design. It wasn’t enough to go on as I had been, happily working piecemeal however it took my fancy. I started to think very hard about creating a environment for the 300 designers who already worked throughout the company, in order to foster a shared awareness and a sense of belonging. I also made up my mind to ensure that design would take a leading role in company-wide initiatives. For example, in terms of career paths. I was told that it was the Head Office that progressed career paths, deciding how an individual would move, and what skills they would acquire by doing what sort of work, and was instructed to put together a plan for each type of professional skill. Right, I thought, let’s submit the plan for design careers first. I began by calling the managers together to talk about it. Of course, there was opposition. I was banging my fist on the desk as I argued.

Another idea was to increase the level of recognition of design. This was greatly influenced by my own career progression. I wasn’t any good at design, and knew very little about it. And that was why I knew we had a lot of people who were very good at it. They had a fantastic amount of potential. So if we could do things in the right way, the scope of their discretion could be expanded. That required the creation of an environment in which this could happen. I had to make it known company-wide, throughout Matsushita, that we were a skilled professional group. So I had to engage in in-house PR. I founded the in-house magazine Create and published monthly issues.

I came to realize that designers could be more proactive. One example was in sales support work, for which design departments provided some of the people involved. That involved going out to shops and selling products. The people we sent out weren’t particularly high-flyers, but they all got amazingly good results. I think this must have been because of their design experience. It gives them something like an affinity for the reality of daily life or a sensitivity to ambience, which are abilities that have to be helpful for sales. That’s because rather than focusing on trying to sell things, what designers look at first is how the user lives.

Create, the in-house design information magazine, first published in February 1982

Designers in an organization

In an organization, the logic of numbers has to be at work. We were 300 or 400 designers among tens of thousands of engineers. At that scale, we had almost no visibility within the company as a whole. Plus, our work was scattered in different locations. Because the company structure is based on business divisions, designers basically belonged to a particular business division, and worked under the head of that division. The circumstances also varied between divisions, with some places having as many as 30 designers and others as few as three. I did once petition for all these designers to be brought together under a single organization, but was brushed aside. It may be that the time wasn’t ripe for it. Later, I did manage to make it happen, but that brought its own problems.

The Industrial Design Center wasn’t an organization covering all the designers, but was rather responsible for managing the shared aspects of design departments throughout the company, like recruitment, human resource management, education, and training. It also handled external affairs. That included lectures and promotions, as well as relations with the Japan Industrial Design Promotion Organization [the current Japan Institute of Design Promotion], including the G-Mark. Within the Center, we established a G-Mark Committee and set up a system for getting managers in each business division to recommend candidate products, and involving them in selecting from among products recommended. We also provided design services for large projects that had not yet achieved business division status, as well as for business divisions that lacked their own designers. A unified designers’ organization is not necessarily the ideal, and it may even be impossible to achieve, but I thought that we must at least prioritize horizontal links between designers in order to keep us all energized. I created opportunities for designers to meet and network in various ways, including design forums and corporate design conferences.

When I was appointed head of the Corporate Design Center, I started the MOVE90 project. Once a year, the designers in all the different business divisions made models of new ideas that had not yet been turned into products, and held an exhibition. Then we dragged in the company president and business division heads to see them. There are all sorts of barriers to product development, particularly when people in sales and marketing say, "If you make something like that, it’ll never sell." But someone in top management saying "That looks all right to me" can get you over that barrier. We did this for five or six years from 1990.

The αTUBE color monitor (1984), produced in response to the new "floor life" lifestyle.

At the time, Naito was coordinating designers as the head of the Design Department in the TV Division.

"Beauty" in the corporation

As we entered the 1990s, the company president declared that we should be "making more design-oriented products." He decided this would be a good theme for a talk at a meeting with the presidents of associated companies, and of course it came down to me to make the talk. I always think that within a corporation, talking about "beauty" tends to imply products or services that target women and children. So this is what I said at the outset. "You all think you know the way the world works, and you probably think that design is all about how to please women and children. But go out into the city, go into bars, go into restaurants. You won’t find many that suit your own style. Instead, you’ll find plenty of places that are a good fit for women, for students, or for children. There’s a dissonance between us and those places, so we have to make an active effort to take notice of them." It was a scary talk to make!

The MOVE96 exhibition

In fact, Naito’s words have been included in The Executive’s Book of Quotations, a collection of sayings bringing together the thoughts and ideas of world leaders: "Everything is in a process of change, nothing endures. We do not seek permanence."

Interviewer/editor: Keiko Ueki, Nakanoshima Museum of Art Osaka Planning Office

* Titles omitted in profiles, annotations, and supplementary explanations set in parentheses in interview articles

Naito Masatoshi passed away last fall. We are grateful for his immense assistance with this project, and offer our sincere prayers for his eternal repose.

This Designer Testimony series presents digests on specific themes from the oral histories being recorded for the Industrial Design Archives Project (IDAP). IDAP plans to publish its oral histories in detail in reports and other formats.