Industrial Design Archives Project

Industrial Design Archives Project

Designer Testimony 06

A new business system— Industrially-produced home interiors

Masuji Hideo

Born in Ueno City (now Iga City) in Mie Prefecture in 1948. Since joining Sekisui House, Ltd. in 1971, Masuji was engaged almost exclusively in planning, development, marketing, and other areas of product development, and served as General Manager of the Interior System Development Department and Product Development Department. After working for Sekisui House for thirty-seven years, he left his position as Management Associate Officer and General Manager of the Product Development Department to establish Office Amaterasu Co., Ltd. In the late 1970s and the 1980s, Masuji built Sekisui House’s Interior Coordination System as a business system for interiors, and launched an era of homebuilder-led product development by driving the development of Sekisui House’s original interior finishing materials and fittings. Researching evolving consumer behavior and perceptions of product value, he constantly strove to develop new manufacturing paradigms in tune with the changing times. He is currently engaged in consulting and supervising business and product development in the fields of home construction and home building materials and fittings.

Building material manufacturers in Osaka

Wood-based building material manufacturers that have grown into sizable enterprises in and around Osaka include Panasonic, Daiken, Eidai, and Asahi Woodtech. The industry took off when a number of companies started processing Osaka Bay’s timber stock. Panasonic (Life Solutions) and Daiken don’t have major plants in Osaka, but grew big on the back of the efforts of their Osaka sales operations. All four of these companies existed before the war, but they really began to grow when they started producing wood building materials for postwar reconstruction. Panasonic, Daiken, and Eidai went on to become diversified building materials and equipment companies by adding components such as kitchen and bath units to their lineups. Asahi Woodtec focused more exclusively on wooden building materials, eventually specializing in flooring, driving the flooring industry on the strength of its products. Many homebuilders (prefabricated house manufacturers) also became major enterprises in Osaka, including industry leaders such as Daiwa House, Sekisui House, PanaHome (Note 1), and Sekisui Chemical (under the Sekisui Heim trademark). I don’t know exactly why Osaka-based wood building materials/equipment manufacturers and homebuilders achieved such success, but Osaka was undeniably at the forefront of the housing and house-building material markets in postwar Japan.

Note 1: PanaHome is now Panasonic Homes Co., Ltd., a group company of Prime Life Technologies Corporation

Building material suppliers had existed from at least the Meiji era (1868–1912), but until homebuilders emerged, their customers were almost exclusively the carpenters who were the lead contractors in traditional house-building, weren’t they? In other words, their products would more suitably be described as crafted rather than manufactured products.

Before the war, processing timber to order was the key modus operandi of the building materials industry, which was divided into general building material merchants that supplied timber studs and other structural and peripheral elements, and so-called precious timber merchants that supplied carpenters with alcove pillars, ranma transoms (openwork dividers) and other ornamental elements.

Demand for plywood and wood fiber board grew dramatically in the postwar reconstruction period, and factories for producing such materials mushroomed throughout the country. All sorts of printed and coated plywood board and flooring products also began to appear, and because of the huge demand for these new building products as both interior and exterior materials for homes being built throughout Japan, their production began to dominate the building materials market.

So building material manufacturers preceded homebuilders, but printed plywood, wallpaper, and other new building materials used in homes were apparently all imported at first, since they weren’t yet being manufactured in Japan. Is that correct?

Initially, homebuilders used the same printed plywoods that carpenters were using at the time. For example, Sekisui House, which was established in 1960, didn’t use such printed plywoods in its earliest products such as its Model A and Model B houses, since its ideal was to create a new generation of building materials to replace plywood and printed plywood. However, it ended up using huge amounts of such existing products because that’s what people were familiar with, and they cost less. That was the situation at the start, but things began to change after that when wall and floor materials started to be industrially manufactured. The rise of the prefabricated housing industry is a story about mass-producing housing materials to mass-produce houses, isn’t it? The aim was to create affordable housing for all the people migrating to cities. Industrially-produced housing seemed the best way to go. However, the first examples were hardly the kind of houses that customers were looking for. They were inferior to houses made by carpenters, and that’s why the word “prefab” acquired negative connotations such as basic and cheap that have stuck to this day.

Around 1960, when prefabricated houses were born, postwar reconstruction gave way to a full-scale housing construction boom that fueled explosive growth in the number of self-employed carpenters. Also, Japan’s Government Housing Loan Corporation (now the Japan Housing Finance Agency) started providing government mortgages in 1950, and prefabs emerged to meet demand at a time when taking out a mortgage to buy your house was going mainstream. At that time, prefab homebuilders were often put down as amateurs, and the fact is that we were all very much newcomers from other industries such as steel, textiles, chemicals, and timber. Daiwa House was a timber company in Yoshino, and Sekisui House split off from Sekisui Chemical, so was originally a chemicals manufacturer. So it was companies like this from various other industries that entered the housing construction industry and started growing their businesses. This is when the concept of mass-producing houses took off. A maxim of industrial production is that you have to make a lot of products to turn a profit.

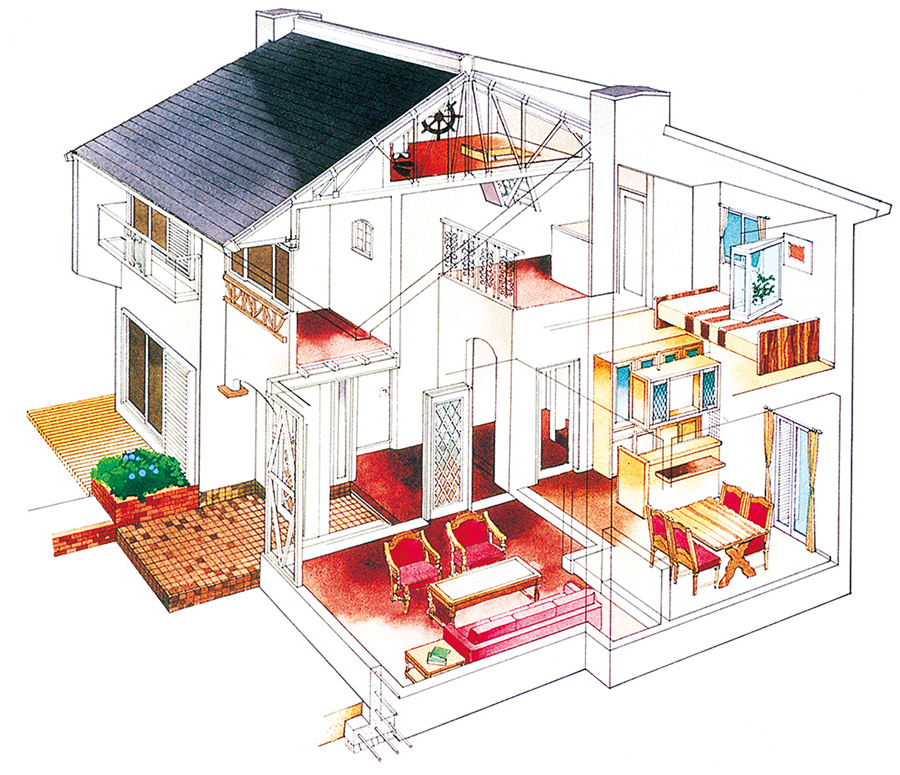

An early Sekisui House interior, embodying the company’s pursuit of prefab housing using new materials

But there were already major construction companies, weren’t there? Was it just that general contractors and similar companies were not involved in housing because building houses was not that kind of industry?

Yes, housing construction was a different kind of industry. It was often referred to as a gori industry, gori meaning five leagues in traditional parlance, which translates into about twenty kilometers in modern terms. In other words, houses were almost all built by carpenters living within a twenty kilometer radius of the site concerned. There were even whole villages built by a single carpenter who had built one house after another. Actually, that was more often the norm. If you go further into the past, to times before a carpenter could be found in each village, the whole village joined hands to build houses. That was just the done thing. It was only after WWII that the concept of mass-producing houses was born, and companies that were used to manufacturing lots of products with low profit margins entered the market.

It was the shortage of housing in postwar Japan that made mass production a necessity, wasn’t it?

Yup. That and the buoyant atmosphere in the heyday of Japan’s rapid postwar economic growth when people began to earn enough money to entertain the idea of owning their own home. I think it was a major advance for housing construction to become an industry geared to churning out affordable homes that made people happy.

One of the biggest reasons for the housing shortage was the migration of people to the cities, wasn’t it? Owing to the increasing number of jobs in secondary and tertiary industries, people relocated in droves.

I think various factors—wealth, political issues, and such like—affected perceptions of the family home. The migration of people to the cities with the shift in socioeconomic structure to secondary and tertiary industries was undoubtedly a major driving force behind the growth of the housing industry, but advances in transportation that reduce travel times were another big factor impinging on the way people thought about their home. Think about it, moving from Osaka to Nagoya or Tokyo. In the old days, it took ten hours to travel to Tokyo, so if the whole family moved, it felt very permanent, but in more recent times, people thought little of making business trips to Tokyo and then heading back, or spending a few years there and then coming back to the family home. Our concept of home is therefore greatly affected by a variety of contexts and factors.

The place where you live becomes your base, doesn’t it? The form of your “home” changes according to how you think of it.

In my mind, industrialization is not an easy concept to apply to housing. Industrial products are made in factories by manufacturers who then supply them to customers as finished products. Houses, however, only ever become finished products after they’ve been assembled on site (the customer’s land). What’s more, no two houses are exactly the same in most cases. Homebuilders present customers with a choice of components, and which components are used in which way depends on the customer and differs from house to house.

When Sekisui House first submitted an entry for the Good Design Award program, we had an argument with the judge over customization. In the past, there was a custom component genre in stereo equipment that enabled consumers to customize their purchase within a range decided by the manufacturer. The Good Design Award judge argued that house customization fell outside that category, saying that because houses are built by assembling all sorts of parts, maybe 50,000 or 100,000 in all, each finished product is different from any other, disqualifying houses from the Good Design Award program. Since there is no single finished form, the only way of including housing in the Good Design Award definition would be to judge the individual houses one by one.

In that case, you would have to decide which individual house to give the award to, right?

Right! So we attempted to counter that position by using the term “system design.” At that time, we were trying to get our IS model certified, and our argument was “This product has been designed using this system, so design is guaranteed.” However, this didn’t wash at first. We finally won a Good Design Award in the third year with help from the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) (Note 2). This judgment basically accepted our system design argument, but still insisted that the assessment be conducted by inspecting a specific individual house of our choice. Despite that, we were allowed to apply the Good Design logo to the system as a whole. It was maybe three or four years prior to this that a car won a Good Design Award for the first time. There were apparently arguments over that too. Under MITI pressure, the Good Design Award program was gradually expanded to include cars and then houses and so on, but the time it took is perhaps indicative of how difficult it was to evaluate and define industrial design and its scope.

Note 2: Now the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI)

IS Flat, the industrially-produced home that won Sekisui House’s first Good Design Award

So from that time on, the definition of “industrial” and what could be seen as industrial design effectively became blurred?

At that time, homebuilders developed ranges of floorings and window fittings and the like specifically for their own use. Each house would then be assembled from that portfolio of components. Later, building material manufacturers began to make products that mimicked those designed by homebuilders. But the building material manufacturers would plan, design, and manufacture flooring simply as flooring, and windows, doors, and other joinery simply as joinery. They didn’t bother themselves with coordination. They produced various items simply as standalone products, and it was carpenters that bought and assembled these products. Homebuilders like Sekisui House and Misawa Homes designed homes with a certain concept in mind, and set limits on the acceptable combinations of components, so their houses were essentially different from the kind that carpenters made by buying this and that component and assembling them. As such, you would be hard pushed to call the houses that carpenters made industrial products.

Building materials are industrial products, so the houses that carpenters build using those materials are undoubtedly made of industrial products, but each and every house that they build is different. Customization within a predetermined range is a foreign concept where such houses are concerned. The lack of such predetermined customization means that the finished product usually varies greatly according to the whims and skills of the architect or coordinator. In this respect, homes are difficult to fit into the concept of industrial products.

The difficult thing is that the building materials and fittings made by building material manufacturers are undeniably industrial products. When Sekisui House uses this and that building material to make a specific house, in our perception, that house is an industrial product, but if a carpenter were to use exactly the same materials to build much the same house, would we call that house a industrially-produced product? Even if it happened to be the same, the process by which it was built was very different.

If a carpenter builds a house using flooring and other materials made as industrial products, that house would still be seen as being built according to traditional methods, even today. In this respect, it perhaps resembles cooking. It’s like someone using industrially-produced ingredients and semi-finished products to cook dishes for the dinner table.

From the homebuilder’s perspective, joinery, flooring, and other interior fittings are no more than parts, but from the building material manufacturer’s perspective, they are products in their own right, each and every one of them. The homebuilder’s product, on the other hand, is the home itself, including the interior, exterior, and structural frame. That’s a big difference.

Then there’s the matter of who designed the product. In the case of building material manufacturers, it’s their designers who design their products. Did those designers ever think about coordination?

I don’t think so. Things probably started to change around 1980. In 1980, Sekisui House launched a new interior coordination system. I happened to be responsible for it. This was the Sekisui House Interior Coordination System (SHIC System). Although we called it a coordination system, it was actually about more than just coordination. If we had just made a system for bringing items together in attractive combinations, the impact on interiors wouldn’t have been so great. SHIC went far beyond just combining various parts, serving rather as a homebuilding business platform on which we developed and manufactured floorings, joinery, wallpapers, modular kitchens and bathrooms, you name it, and including systems for customer presentations, parts distribution, and other components. Whether SHIC was a good or bad idea is another matter. Looking back, there are plenty of aspects that I think we would have been wise to leave alone. Even so, the Sekisui House of today is still running on the rails we laid with SHIC forty years ago. It’s probably about time they invented a new system more in tune with the times. Anyway, the first thing that the SHIC System improved was design. By design, I mean all plans required to meet the wishes of customers. This of course includes flooring, walls, and other interior fittings. That, and design presentation. This was enhanced with SHIC. Another thing was the standardization of on-site construction. The way everything fit together—for example, the way a skirting board was to be fitted when this and that element were joined—was all decided in advance.

Overview of Sekisui House’s SHIC System

In other words, whereas carpenters tend to fit things together on-site, making adjustments as they go, all Sekisui House parts are coordinated to fit together in advance.

We even made the adhesives used at our house construction sites. That kind of thing improves the on-site construction process.

Once you have your design and coordination, you can provide a precise estimate. Carpenters these days also provide clear estimates, but in the past, their estimates were often very much guesswork. Homebuilders can provide very exact estimates because each part has a part number and price tag. In Sekisui House’s case, when estimating using the SHIC System, we could even accurately list man-hours in the estimate, since we’d actually timed how long it takes to install each part.

So you can even come up with precise labor costs?

Correct. Everything can be calculated. That’s the essence of this system. So, for example, you can tell at a glance how long it will take to lay the floorboards of a six-tatami room (approx. 10 m2). That’s why our estimates were so precise.

Another strength is original building materials. These are materials such as flooring or joinery that are produced exclusively for Sekisui House by manufacturing partners. From the start, the idea was to use original materials for everything, rather than stuff that was already out there on the market. In those days, there was no way of making quality houses with commercially available products. So, even if it involved the lot of trial and error, whenever we wanted a certain building material or part, we would plan and design it from scratch.

It was in the 1980s that the relationship between building material manufacturers and homebuilders changed, wasn’t it?

We switched to original products for everything—flooring, carpets, joinery, wallpaper, fittings, storage, you name it. We insisted on everything being original and exclusive to Sekisui House.

How did that work out cost wise?

There’s the rub. Original products cost more than the general products on the market. Sekisui House is a strange company. I think it was in 1981 when I took some new original products to a branch for them to sell, and they said, “Okay, just leave them there.” They treated the parts just like those of any other building material manufacturer. It didn’t matter that they were original Sekisui House parts; they got no preferential treatment. It was left completely to our sales branches to choose parts that would most benefit their customers and their own bottom lines.

So does that means you had to compete with other building materials, irrespective of yours being original products?

That’s right, but happily, we managed to win in the end despite being expensive. Quite frankly, I think it was because our products were of superior design. That and the money aspect. Our products made pricing much more transparent. It took about a year, but eventually everyone in the company came to appreciate that our products were better even if they were expensive, and they stopped selling other products. If they hadn’t, our coordination system would have soon been scrapped. And I don’t think it would be too much of an exaggeration to say that the interior design of Japanese houses would not have evolved the way it did had it not been for SHIC.

So this system owes its success not only to the design of original building materials, but also to the clarity of estimates, and feasibility of cost calculation. This all helps to reduce losses and risk even if the prices are higher than average, and with the visibility provided by your construction process, the houses are also easy to sell, right?

Well, yes, such things make our products easy to sell. Another thing that still happens quite often is that people will say, for example, “If it’s only a difference of 500,000 yen, we’d prefer this.” In other words, our original building materials were attractive enough to make people want them. And we played to those sentiments by attaching labels such as “Original 5 Star” and creating different ranks of flooring such as standard and high spec, and marketing them in such a way that customers would be tempted to go for the higher grade products. This became the crux of our coordination system.

You wrote the copy for the SHIC pamphlet, didn’t you? Was it around that time that design personnel also got involved in designing such public relations and promotional materials?

Yes. Planning and developing products was our first task, design in the narrow sense. Our designers put a lot of thought into how products looked, while our engineers did the same regarding functions and performance. We also had sales promotion and advertising personnel working hard on communication. But when you come to think of it, all of this falls under design, and you need to have people capable of overseeing the whole process. You have people doing design in the narrow sense, and other people handling communication, but who brings it all together in one product? You need someone working on overall communication. I think of that sort of task as being design in a broad sense, or overall production, if you will. The company’s organization has changed from my day and is a little different now, but Sekisui House’s approach to product development was very much design in the broad sense. That was also the approach we applied to our housing catalogs. Think about it. You can’t expect someone who has never handled our stuff and is just handed a bunch of information to come up with convincing ads. That’s why, if you’re serious about communication, you need to involve people who know the subject inside out and have a good idea about what they want to get across.

SHIC System communication tools

How did you first become involved in interior design?

I joined the company in 1971, and was assigned to the section developing flat-roofed products, our FN models that were just coming out at that time. Rather than development, I was involved in instructing workers on site on assembly of the steel frames. You may think it strange that I was instructing people in my first year, but it was just a matter of me saying stuff like “Please assemble these parts in this way.” After doing that for a year, I helped with the development of other products, and then in my third year went on to exterior design, components like balconies and front porches. At that time, there was no one handling interior decoration. The concept of interior design didn’t exist. We did have a lineup of interior materials, however, and I handled those too, fitting them in around my other tasks. Nothing sophisticated. I was just told to look after interior linings shipped from factories. The wooden linings for flooring and walls were at that time shipped from factories. There were so-called floor panels that were used to make a base platform for flooring, interior wall frames and bases, and what were known as partition frames. That was about all the interior materials we handled at that time. The sales office concerned would buy whatever else was needed from local building material merchants.

I was still young at the time, and got into all sorts of disputes, like the argument I picked with a sales branch deputy manager over his way of doing things. I also got into a really big fight one day at a meeting in Osaka, and was summoned the next morning by the general manager of the Technology Division, my ultimate boss. “You’re always causing trouble fighting with people, so everyone’s better off if you do nothing,” he said. “Hand whatever work you have to the guy next to you. Don’t do anything.” So, I didn’t have anything to do anymore. Then one day, the same division chief who told me not to work summoned me again and told me to go talk to so-and-so. Long story short, it appeared I was being asked to handle interior materials. Not that the division chief said so in so many words. No one—neither Sekisui House nor any other homebuilder—had yet gone into interiors at that time. It was about three months later that I came to realize that maybe we should think of commercializing the field of interior design. I didn’t have anything else to do, anyway. I hadn’t yet thought about how exactly to sell interiors, and just started going around show houses at housing parks, taking pictures of what I thought were attractive interiors, and then organizing the photos into various genres that I could then show people as examples. That was how I started out.

What were other homebuilders doing in interiors around the time that Sekisui House began to commercialize the field?

They were coming out with floorings that were completely new to Japan. Joinery too—in other words, fittings. There was painted joinery, drawer and cabinet front joinery, and surrounding fittings. The first things that we made was joinery with PVC fronts of various designs. Misawa Homes was probably the first homebuilder to use PVC and other such facing materials in the home. I think it was the Misawa Model O in 1976. The main pillar was wrapped in PVC sheet. Everything else too. But the Model O was the only product in which Misawa Homes used PVC sheet to such an extent. Sekisui House used PVC extensively. We covered all sorts of joinery in PVC sheet. Later, we switched to olefin sheet. The emergence of olefin sheet has proved to be a great thing for today’s building materials industry. We made all sorts of original products with olefin sheet—flooring, joinery, carpets, wallpaper, you name it.

Another area in which Sekisui House drove the industry as a whole was the use of drywall for wall lining—the layer below the interior finishing material. We started using drywall in some walls around 1976 or 1977. Then, from our terrace house Model H homes, we used drywall for all wall linings. It was from this point that we began standardizing drywall as our main wall lining. And the widespread use of drywall heralded the arrival of wallpapers as interior finishes. There were very few such materials in the 1970s. Up to then, it was all printed or coated plywood board. That’s why floorboard manufacturers were also the main producers of printed or coated plywood wall paneling. In fact, production of wall paneling outstripped that of floorboards at that time. That’s why, when we developed our original floorings, we also started shifting to wallpaper. I was telling everyone that printed and coated plywood paneling would become a thing of the past. I told building material manufacturers that they better focus on flooring because plywood wall paneling was going out of style. We made a lot of wallpaper from around that time. Nowadays, white wallpaper is in fashion, but in those days, brownish colors and large-pattern wallpapers were common.

While all this was happening, the biggest development at Sekisui House was the creation of our own factory to carry out in-house production of items such as joinery, various fittings, and other original building materials, and modular bathrooms and kitchens. Toilets were the only items we bought on the market. As an example of in-house production, for millwork such as joinery frames and skirtings, we would cover plywood, MDF or other board with PVC sheet, and then cut V-shaped grooves into the board side, leaving just the PVC sheet. Then all we had to do was bend the boards along the grooves to produce stick-shaped components. This is the same as the method used to make TV and audio cabinets. We adopted the process and made equipment for cutting such V-shaped grooves in board. This enabled Sekisui House’s factory to generate tremendous profits. It was management approval of this system that launched in-house production at Sekisui House.

Even if products sell, it doesn’t mean anything unless they turn a profit, right?

Absolutely. No one’s interested unless the goods generate profit.

In other words, things went well in the end because the system worked and enabled the factory to turn a profit, right?

Yes, but things get made even without a system. It just happened that in this case, the system was key, and that set the course for subsequent growth. Even so, no one believed that it was the SHIC System that was the driving force behind the improvement in the company’s design capabilities. You could argue that it was thanks to the system that we started producing original building materials and developing attractive designs, but people would say that’s no big deal, that we were still buying all our stuff from other makers and only turning a slight profit on the goods. It was only once we started manufacturing products in our own factory that turned a profit that people began say nice things about the SHIC System.

Do you think that having such a system is what makes homebuilders what they are?

I think that used to be the case, but moving forward, housing starts are predicted to fall, so I think we need to move on from putting such priority on in-house production, and develop new production and logistics systems.

So do you think homebuilders should perhaps evolve into something like home coordinators?

That may be the answer. Up to now, we’ve generated profit by making stuff, but from now on, we perhaps need to make money more by selling our know-how in the form of house proposals. The demand for housing is likely to decline, so the challenge is to deliver value even as demand declines by providing useful services and outstanding designs.

So you’re talking about a shift from hardware (products) to software (services), and perhaps becoming more agile and versatile?

Yes, that kind of thing. Sekisui House would handle planning and sales, but production would be done by someone else. This resembles the kind of business model used in the apparel and other industries.

Why were the original products of homebuilders superior to those of building material manufacturers? Was it because of the superior design capabilities of homebuilders? Or was it because of the difference in perspective?

I think that the quality of design and the way it matched changing times was the biggest reason, but the difference in perspective probably also played a part. Sekisui House’s development was geared to B2C business, whereas the business model of building materials manufacturers is B2B2C. Their top priority is the B right in front of them, the businesses they deal with, and those businesses are mostly distribution wholesalers. I think of this model as B2b2C. The capital B is the manufacturer. The lower case b next to it might be a distributor or wholesaler, building contractor, coordinator, or architect, but anyway, someone who deals directly with customers and can influence them. So, building material manufacturers are essentially making products for those b people in the middle. In Sekisui House’s case, however, b doesn’t figure in the equation. The company deals directly with the customer C, listening to what customers want, and making stuff that they will be happy with. It was in fact more a case of us getting building materials manufacturers to make things for our customers. Our stance was that if they made such products, we would sell them. I think this is the biggest difference between building materials manufacturers and homebuilders.

Do you think that it was because the SHIC System provided a solid foundation that manufacturing was easy for the generations after yours?

Even with new products, for example, floorboards, we measured everything, including man-hours required to lay the floor. Knowing the price of a single floorboard is in itself not that useful. As an easy example to understand, some flooring uses quite narrow floorboards, and they tend to be a little expensive. The boards themselves may cost 1.2 or 1.3 times an equivalent amount of wider floorboards, but the cost of the whole floor works out as more than double. The reason is that it takes more man-hours to lay. If all such costs are laid out clearly in the breakdown, it’s easy to explain prices to customers. As such, installation man-hours are very important. We started doing this in 1981, and it took about four to five years to become established practice, or in other words, to become the company’s business system. If it hadn’t taken root, if we had ended up simply with a lineup of original building materials, I don’t think Sekisui House could have taken the quality of its interiors to such a high level.

And that is not just a matter of the design being good, but also that it ultimately benefits the customer, right? If that hadn’t been the case, the SHIC System would probably not have had company-wide impact, and things might have turned out differently. You could say that the system took root because it benefited customers, and that it enabled your company to demonstrate a kind of homebuilder design ideal. But what’s happening now? Are there any moves afoot to create a new system?

That’s a very tough proposition. Back in our day, there was nothing to start with, and the system emerged more by accident than by any specific plan or intent to build a system. Now, however, the system is chockablock with existing elements that the company is constantly striving to maintain, so the situation is very different. I quit Sekisui House in 2008, and in my last five years there, I was telling everyone in the company that it was high time they moved beyond SHIC. If they allowed themselves to be ruled by the current SHIC System, they would never be able to come up with anything new. There is nobody now who was around at the start of SHIC, nobody who knows the inside story. That’s why the company needs to come up with something new and make a fresh start. If it doesn’t, it will remain stuck in a groove and nothing will change.

Regarding colors and styles, were there any particular pivotal moments in the history of product development?

As you can tell from looking at SHIC I, the acronym was derived from Sekisui House Interior Color Coordination. C originally stood for color coordination. This was changed to Sekisui House Image Coordination in SHIC II, and to Interior Coordination in SHIC III. First it was Color, and then we changed it to Coordination. This is because we knew that at first, customers wouldn’t have understood what we meant by coordination. Color was much easier to grasp, so we put the emphasis on color.

Do you mean that the word coordination didn’t exist in general parlance at that time?

It was still unknown. In 1983, Mitsui Home led an initiative to establish a certification system for the profession of interior coordinator. Actually, Mitsui Home already had such specialists, and MITI oversaw the process of creating such an interior coordinator education system. Following the interior coordinator qualification, kitchen specialist and other certification systems were also established. When the interior coordinator qualification was established, we argued that no matter how much effort such specialists made, nothing would come of such a system unless good materials were available. That’s why we decided to focus on our SHIC System rather than human resources. However, when Mitsui Home started churning out female interior coordinators, we were forced to follow suit so as to be able to compete at the sales front line. About two years later, the Ministry of Construction (MoC) came out with an “interior planner” certification system as an architect specialization.

How did they differ?

Basically, the difference between the systems aligns with the difference between the ministries. Interior planner was an MoC qualification for first-class architects or their equivalents who had particular strengths in housing interiors, and it was very difficult to earn. Interior coordinator was a MITI invention, so it is positioned as a coordinator of product sales. That’s a big difference.

What does the word “new” mean in this context? Does it refer to products themselves? Or to spaces?

I think it’s products. Design is ultimately aimed at creating new products, in my mind. There are, however, a lot of peripherals or tools that you can use to succeed. Whatever, there’s an element that even the best designers often forget. I’m talking about the customer. When designers are talking, you often hear them saying “Wow, that’s cool!” or “This is something you don’t often see,” and so on, but they really need to be asking themselves how customers are likely to react.

If you really have the customer in mind, you need to think about aspects like energy consumption and cleaning as well. You have to open up and discuss things candidly with customers. Design should really be about resolving problems together with the customer. It used to be that designers could say all they needed to do was look at something to understand it, but nowadays, they need to do a lot more listening and talking. I think there are all sorts of things they would like to tell customers about—what they were thinking when they were designing something, the story behind this or that design, and so on. For example, this wood is walnut. Walnut is a premium wood that’s also actually used to make such and such. That’s the kind of material we chose for this house’s flooring. That’s the kind of thing you want to get across, but more often than not, that detail gets left out. So to me, “new” also encompasses such communication. Customers have nothing to go on apart from their likes and dislikes unless you tell them about the products and their value. The same goes for prices. Any designer who tells a customer that they could get a better product installed if they budgeted another 100,000 yen but can’t explain exactly why that product is worth an extra 100,000 yen is not a designer in my mind.

I’m pretty sure that the designers and developers at Daiwa House, Misawa Homes, and PanaHome also all think the same way. I never had an opportunity to chat with them, but someday I’d like to. In the home appliance industry, the people at Panasonic, Sony, and Sharp all try to make different stuff from each other, but building materials manufacturers all make much the same products in competition with each other. That’s fine if the customers benefit, but I can’t help feeling that homebuilders and building material manufacturers have lost their appetite to compete with each other and come out with new stuff. It could be that we’re just in a period of transition before innovation picks up again. We’ll have to see.

One thing that struck me in particular was the way he repeatedly came back to “the customer.” This is undoubtedly a reflection of his appreciation as a developer of the fact that while building and selling houses is the primary and final goal of homebuilders, those houses are to their purchasers invariably a huge investment that represent a new start to their lives.

Interviewers: Takayuki Nakamura, Life Style Laboratory, and Keiko Ueki, Planning Office, Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka

Interview editor: Keiko Ueki | Photos courtesy of Sekisui House, Ltd.

* This interview was conducted in 2017.

This Designer Testimony series presents digests on specific themes from the oral histories being recorded for the Industrial Design Archives Project (IDAP). IDAP plans to publish its oral histories in detail in reports and other formats.